Robert Del Naja (3D): Bristol, Massive Attack & the Beautiful Resistance

I first encountered Massive Attack in the most unsuspecting way: through the music video for Unfinished Sympathy. On the surface it looked almost simple — a single unbroken shot of Shara Nelson walking through Los Angeles streets. But with my technical knowledge of filmmaking, I knew the difficulty humming beneath the surface. The choreography, the poise, the patience — it carried an elegance that hit me somewhere I didn’t yet have language for. I didn’t fully know what Massive Attack was at that point, but that video compelled me to buy Blue Lines, and once I did, the sound lodged itself into my bloodstream and it never really left.

By the time Mezzanine arrived, I was older, driving, working, and it became a constant loop in my car. There’s something special about having an album become the landscape you move through — every commute, every late-night drive, painted with its pulse. And then there was the Teardrop video. An unborn fetus mouthing the lyrics. Watching it felt like staring directly into a secret I wasn’t supposed to be allowed to see. It blew my fucking mind. That was the moment the scale of Massive Attack revealed itself — the realization that they weren’t just making music; they were building a new mythology for how art could exist in the world.

If Mezzanine was the cathedral, Heligoland was the prayer I kept closest. That album still might be my favorite of them all. There’s a density, a gravity, to Heligoland that feels almost oceanic — like waves endlessly folding back on themselves. It taught me that music can be both heavy and liberating, claustrophobic and expansive in the same breath. It became not just something I listened to, but something I carried inside me.

My love for Massive Attack has only grown since. I’ve lived every album they’ve given us, and I was lucky enough to see them live in New York for my birthday a few years back. It was unforgettable. I bought a tour hoodie that says “Conspiracies are a conspiracy” on the front and on the back “To make you feel powerless.” I still wear it constantly, a reminder stitched in cotton that their politics are inseparable from their poetics.

Looking back, the idea that this was more than music wasn’t instant. It was a slow burn, embers working away in my subconscious until I understood: this was art on the highest level, maybe the most artistic musical act that has ever existed. Robert Del Naja aka 3D — with his multi-faceted faces of art, activism, and design, embodies that truth. He is a creative director, an activist, a systems thinker, and a kindred troublemaker whose work forces you to think. And yes, the whispers about him being Banksy only add to the legend — if it’s true, then we’re talking about the greatest living artist of our time.

For me, Del Naja’s work is like embers waiting to rage into fire. Slow, patient, impossible to ignore. And when I think of him, I think of Bristol — not just as a city, but as an origin myth, a place where subcultures found their pulse and broadcast it worldwide. That pulse still radiates outward.

Why write about him now? Because more people need to understand this standout creative — what he does, what he stands for, why his work matters. Sharing these inspirations is how we pass on the keys to the universe. Just as Massive Attack shook up music, visuals, and politics, at RIOT we aim to shake up an entire industry — to show that you can do things differently, disruptively, and beautifully. This piece isn’t just about him. It’s about what’s possible when art refuses to stay in its lane.

Bristol, Stencils, Beginnings

Before the world knew him as 3D, Robert Del Naja was a shadow with a spray can. Bristol in the late ’70s and early ’80s was a city in flux — shipyards closing, unemployment biting, a multicultural population simmering with both tension and creativity. The walls became canvases for protest, pride, and play. And it was here, under the orange sodium haze of the streetlamps, that Del Naja began writing himself into the city’s bloodstream.

He was one of the first British artists to make stencil graffiti a language. Where others free-handed tags, Del Naja carved precision: silhouettes, icons, fast images designed to go up quick and leave a lingering afterimage. In Henry Chalfant and James Prigoff’s seminal book Spraycan Art (1987), Del Naja appears as one of the few UK artists featured — a teenager whose work already carried both urgency and aesthetic clarity. The BBC documentary Bombin’ (1987) showed him alongside the Wild Bunch crew, tracing the exchange of graffiti culture across the Atlantic. Bristol wasn’t New York, but it was listening hard, and Del Naja was helping it translate.

“We all grew up listening to punk and funk. That attitude snuck into everything.” — Robert Del Naja

Artwork by Robert “3D” Del Naja for Massive Attack’s Heligoland (2010), Virgin/EMI Records. Used here for critical commentary and linked through to the official album release.

The punk records blasting through bedrooms collided with imported hip hop, reggae sound systems, and the dub echoes of Jamaica carried in by the city’s Caribbean community. This collision became the Wild Bunch, a sound system collective that gathered Del Naja, Grant “Daddy G” Marshall, Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles, DJ Milo, and a young Tricky into its orbit. They weren’t just throwing parties; they were shaping a new grammar — sonically and visually. Del Naja MC’d, designed flyers, painted walls, and gave the crew a face as distinctive as its sound.

What mattered in those early years wasn’t polish but presence. Bristol’s scene thrived on hybridity — punk’s DIY ethic, hip hop’s collage mentality, reggae’s bass pressure, and the raw politics of a generation staring down Thatcher’s Britain. Del Naja’s graffiti carried the charge of all of it: fast, defiant, and iconic. Each stencil was a kind of fugitive manifesto — art that existed in public, often illegally, but claimed space as if it had always belonged there.

By the mid-’80s, 3D was already a legend in Bristol’s underground. He’d left his fingerprints on walls, record sleeves, and dance floors, creating a template that blurred boundaries between music, visual art, and political intervention. The seeds of Massive Attack were sown here, in the damp brickwork of a port city and the restless energy of a youth culture that refused to stay quiet.

Blue Lines & the Birth of a Sound

When Blue Lines arrived in 1991, it didn’t sound like anything else on Earth. Built from crate-dug samples, dub basslines, hip hop breaks, and soul vocals, it moved at a slower tempo than the club music of its day. It wasn’t built for the dance floor — it was built for the bloodstream. The press called it trip hop, a term Massive Attack themselves never fully embraced, but one that stuck to the Bristol Sound like smoke. Whether they liked it or not, they had just invented a genre.

Recorded in just eight weeks at Coach House Studios in Bristol, the album was an exercise in resourceful invention. Reel-to-reel tape machines, Akai samplers, and a modest budget forced the group to turn scarcity into alchemy. They borrowed from the deep crates: Tom Scott’s “Sneakin’ in the Back” laid the foundation for Daydreaming, Isaac Hayes’s “Ike’s Rap II” was reborn as One Love, while the likes of Wally Badarou and the Mahavishnu Orchestra surfaced in new disguises. It was hip hop’s sampling ethos crossbred with dub’s echo chamber and Bristol’s own restless hybridity.

Unfinished Sympathy was the lightning strike. Shara Nelson’s voice lifted by a 40-piece string section, anchored by a rolling hip hop rhythm, its ambition was orchestral and streetwise at once. The music video — a single continuous tracking shot through Los Angeles streets — captured the paradox at the heart of Massive Attack: apparent simplicity hiding enormous complexity. It’s the same video that pulled me into their orbit, and it remains one of the most iconic statements in modern music history.

The album’s other corners revealed the crew’s full spectrum. Safe From Harm pulsed with defiance, Grant “Daddy G” Marshall’s baritone grounding it in gravitas. Daydreaming rode a smoky loop with Tricky’s unmistakable presence, hinting at the solo career he’d later carve out. One Love leaned on Horace Andy’s timeless tenor, a voice that would become Massive Attack’s secret weapon across decades. Every track felt like a different doorway into the same warehouse, each room lit differently but connected by the same bass hum beneath the floorboards.

NME declared it “the album of the ’90s” almost as soon as the decade began. Others hailed it as a masterpiece of atmosphere and mood, a work that didn’t just soundtrack the early ’90s but seemed to redraw the map of what British music could be. It was proof that innovation didn’t have to come from London — that Bristol, with its multicultural stew of Caribbean sound systems, punk ethos, and post-industrial shadows, could generate a new sound-world entirely its own.

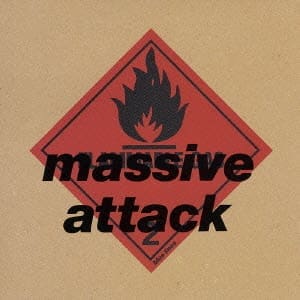

Album artwork for Massive Attack’s Blue Lines (1991), designed under Robert “3D” Del Naja’s visual direction. Virgin/EMI Records. Used here under fair use for critical commentary.

The context mattered. Bristol had been marked by unrest a decade earlier: the St Pauls riot of 1980, sparked by police raids and systemic inequality, left scars that bled into its art. The city’s creative community answered with sound systems, murals, and underground parties — grassroots ways of reclaiming public space. Blue Lines carried that history in its DNA. It wasn’t protest music in the traditional sense, but its very existence was political: Black and white artists, men and women, voices and beats all woven together in defiance of rigid categories.

Visually, Robert Del Naja was already establishing the language that would define Massive Attack for decades. The Blue Lines sleeve set the tone visually: a brown cardboard backdrop stamped with a red hazard diamond and black flame icon, the words “massive attack” printed in bold across the warning. It looked less like a record cover than the packaging for combustible material — a manifesto of industrial minimalism that would become Del Naja’s signature. It wasn’t decoration; it was a label, a code, a statement of intent. Flyers and posters bore his stencil scars, political undertones, and an aesthetic that made the image inseparable from the sound. Del Naja treated visual design not as packaging, but as another track on the record: an argument, a clue, a code.

Blue Lines was a barometric shift. With it, Massive Attack announced themselves not as musicians in a band, but as architects of a new cultural climate — one where bass carried the politics and silence could be as powerful as noise.

Between the Lines: Art in Transition, 1991–1994

Massive Attack’s debut cracked open a sound-world, but for Robert Del Naja the years between Blue Lines (1991) and Protection (1994) were as much about images as about songs. If the music was the bloodstream, his artwork was the nervous system, firing signals that stitched meaning through every release.

The post-album releases carried his unmistakable stamp. The Safe From Harm single cover featured a close-up of a UK plug socket, typography stamped across it in bold type. Mundane object as cultural artifact, electrified by design. The Be Thankful for What You’ve Got EP, meanwhile, arrived with a surrealist touch: two worms curling against a textured surface, framed by the band’s hazard-flame logo. These were visual passwords, a graphic system that told you Massive Attack was more than a band. It was an atmosphere.

During this period, Del Naja was also shifting his graffiti practice from walls to studio canvases and mixed media. The urgency of street work remained, but he began treating pieces as archival — objects that could travel, endure, and be shown beyond the impermanence of the street. This wasn’t a retreat from the rawness of graffiti, but an expansion: a way of evolving the stencil ethos into a broader visual language.

Politically, the art grew sharper. Symbols of surveillance, militarism, and propaganda started to surface in his work — warning signs of the thematic weight that would define Protection. He was beginning to treat every visual decision as an intervention: the choice of a typeface, the starkness of a color, the deployment of an icon. Each element said: pay attention.

Meanwhile, the Bristol scene was fermenting. Tricky, who had appeared on Daydreaming, was preparing his own solo work, and the city’s creative energy kept spilling into new mutations. Del Naja was at the center of it — MC, painter, designer, provocateur — a figure whose multiple identities seemed to feed off one another.

By the time Massive Attack began shaping Protection, the visual vocabulary was already alive. Hazard diamonds, stark lettering, political undertones — these weren’t just design flourishes. They were the connective tissue of a project that was always bigger than music alone.

Protection: Shelter and Shadows

By 1994, Massive Attack had to prove they weren’t a one-off Bristol anomaly. Protection was the answer — an album less about the shock of invention and more about building an architecture around the world they’d just cracked open. If Blue Lines was a manifesto, Protection was the perimeter: slower, subtler, less about impact and more about atmosphere.

The title track set the tone. Tracey Thorn — best known as the voice of Everything But the Girl — delivered a vocal that was both maternal and unflinching, protective in the truest sense. It was an inspired choice: Thorn’s alto cut through the haze with a clarity that felt like steel wrapped in velvet. Horace Andy returned, his ethereal tenor floating across Spying Glass and Light My Fire, while newcomer Nicolette brought an experimental edge to tracks like Sly and Three. Each guest voice was carefully chosen, not as decoration but as architectural support — beams in the structure.

Sonically, Protection leaned warmer than Blue Lines, with Adrian Utley of Portishead contributing guitar textures and Craig Armstrong orchestrating strings that swelled without overwhelming. Dub basslines still anchored everything, but the mood was more nocturnal, more reflective. If Blue Lines felt like a city breathing in the daytime, Protection was its after-hours double — the soundtrack to midnight taxis, rain on sodium-lit streets, the hush between last call and first train.

Visually, Robert Del Naja tightened the screws. The hazard-diamond language became sharper, the typography more austere, the political undertones bolder. The Protection sleeve, with its warning-label aesthetic, wasn’t an afterthought but an extension of the music’s atmosphere. Like the songs, the artwork was about boundaries — fire warnings, caution signs, the semiotics of risk. It was a graphic perimeter around sound.

Portishead’s Dummy dropped the same year, Tricky’s solo career was beginning to stir, and suddenly Bristol wasn’t just a city. It was a scene, exported worldwide. Massive Attack were still reluctant leaders of a genre they’d never claimed, but their influence was undeniable.

Critically, Protection was well received, though often cast in the shadow of its bookends: the revolutionary Blue Lines and the dark bloom of Mezzanine. Yet for many fans, this is the most listenable Massive Attack record — the one that lingers in kitchens at 3am, that soundtracks drives through wet streets, that makes vulnerability sound like strength. It’s less about spectacle, more about shelter.

Protection solidified what Massive Attack were becoming — a space you could step into and breathe differently. And at its center was Del Naja — choosing fonts and symbols as carefully as samples, making sure the art and the sound spoke the same coded language.

Fault Lines: 1994–1998

The years after Protection were less about consolidation than fracture. Tricky, restless and mercurial, left Massive Attack to launch his own solo career. His 1995 debut Maxinquaye was an instant classic, proof that the Bristol Sound wasn’t a single band but a continuum of voices. His departure left a gap, but it also gave Robert Del Naja more space to steer Massive Attack’s aesthetic compass.

Del Naja doubled down on visual work during this period. The hazard-diamond language that had defined the early sleeves sharpened into something colder, more industrial. In his studio practice he moved toward canvases and mixed media that fused political iconography with biological unease: surveillance motifs, fragmented faces, insect forms. The atmosphere was mutating from protection into threat. You could already feel Mezzanine taking shape, years before a note was released.

The mid-’90s also saw Massive Attack step deeper into remix culture and soundtrack contributions, where Del Naja’s hand remained visible. Singles like Karmacoma were released with artwork that carried his distinctive edge, while collaborations bled outward into film scores and remixes that spread their influence beyond Bristol’s borders. The music was in flux, but the visuals never wavered: every artifact arrived coded, stamped with 3D’s fingerprint.

On the technical side, Del Naja began experimenting with projections and stage ideas that hinted at what was to come. Typography behaving like light, statistics as scenography — seeds of the collaborations with United Visual Artists that would later define the live Mezzanine experience. Even in rehearsal spaces, he was already thinking of concerts as laboratories for visual propaganda.

By 1997, the fractures were widening. Long-time member Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles grew increasingly uncomfortable with the darker direction the band was taking, while Del Naja leaned into it with conviction. The next album wouldn’t be protection, or shelter, or even perimeter. It would be something else entirely: a black bloom, a bassline with teeth. Mezzanine was waiting in the wings.

Mezzanine: Dark Bloom

By 1998, Massive Attack no longer sounded like the protectors of anything. Mezzanine was rupture: an album where basslines gnash their teeth, guitars scrape at the walls, and voices drift through like ghosts caught in an industrial fan. It was a reinvention, a declaration that Massive Attack could mutate into something darker, sharper, and even more vital.

The opening track Angel sets the tone immediately: Horace Andy’s fragile tenor floating over a bassline that grows like a tidal wave until it swallows the room whole. Risingson follows with dub murk and whispered menace. And then comes Teardrop — Elizabeth Fraser of Cocteau Twins breathing vowels that sound like weather, paired with a rhythm that feels both mechanical and heart-born. The music video, featuring an unborn fetus lip-syncing Fraser’s voice, remains one of the most unsettling and unforgettable visuals in modern music. It crystallized what Del Naja and Massive Attack were doing: turning pop into something uncanny, intimate, and cosmic all at once.

Inertia Creeps pushed even further — a claustrophobic meditation inspired by Del Naja’s own insomnia, where beats shudder like nervous systems. Elsewhere, Group Four (again with Fraser) and Dissolved Girl carried the tension to cinematic extremes. This was not background music. It was architecture you lived inside, heavy and sublime, built from loops, distortions, and shadows.

The album’s cover sealed its mythology: a stark black beetle rendered by Del Naja, at once reliquary and warning. A fossil from a future already collapsing. Inside, the artwork leaned into fragmentation — faces cut into xerox fragments, surveillance motifs, digital noise. Mezzanine wasn’t just listened to. It was inhabited, visually and sonically. Del Naja’s art made sure of that.

Live, the band’s transformation was even more dramatic. Early experiments with projection evolved into full-blown anti-propaganda systems. Typography flared across screens like state warnings. Statistics were turned into light. You could see Del Naja’s obsession with turning concerts into information warfare, spaces where the spectacle wasn’t distraction but confrontation.

The making of Mezzanine was fraught. Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles hated the new direction, and his departure during the recording confirmed that this darker, more abrasive Massive Attack was Del Naja’s vision. It wasn’t easy music. It wasn’t meant to be. But its difficulty was its power — and its lasting legacy.

Critics hailed Mezzanine as a masterpiece, though its departure from the warmth of Blue Lines and Protection made it polarizing for some. Over time, its influence only grew. Tracks found their way into films, television, and video games; its atmosphere reshaped how popular music could feel. The album stands now not just as Massive Attack’s most iconic work, but as one of the defining records of the 1990s — proof that art can be both beautiful and terrifying in the same breath.

Mezzanine remains a dark bloom in the cultural memory: an album that revealed Del Naja at full force as not just a musician or painter, but as a systems-builder. Sound, image, politics, live performance — everything cohered into a singular world. Step inside it, and you weren’t the same on the way out.

100th Window: Cold Architecture

The fallout from Mezzanine was as dramatic as the music itself. Andrew “Mushroom” Vowles, uncomfortable with the band’s turn toward darker territory, left Massive Attack during its recording and never returned. Daddy G took a step back around the same time, leaving Robert Del Naja to shoulder the project almost alone. In their place, Del Naja found a new axis: producer Neil Davidge, who would become his closest creative ally for the next decade. The shift marked the beginning of a new era — one where Del Naja’s vision, sharpened by fracture, became the dominant engine.

The result was 100th Window (2003), the coldest, most austere Massive Attack record. Where Mezzanine had bristled with distorted guitars and haunted vocals, 100th Window stripped everything back to a digital skeleton. The beats were skeletal, the atmospheres clinical, the space between notes heavy with paranoia.

Sinead O’Connor’s voice haunted two of the record’s most striking tracks — What Your Soul Sings and Special Cases — bringing a spectral humanity to the otherwise glacial sound. Horace Andy returned once again, his high tenor an anchor in the storm, this time set against cold electronics rather than dub warmth. Tracks like Butterfly Caught and Future Proof pushed further into claustrophobic territory, marrying glitch, minimalism, and an almost forensic precision.

The recording process itself reflected Del Naja’s obsession with detail. Early sessions were scrapped, songs were deconstructed and rebuilt, often multiple times. Digital editing became not just a tool but an aesthetic. The album took four years to complete, its perfectionism a symptom of both Del Naja’s control and the band’s internal fractures.

Visually, the artwork matched the music’s austerity. Gone were the organic stencils and insectoid relics of Mezzanine. In their place: icy fragments, blurred faces, visual noise that felt like CCTV footage and corrupted code. Del Naja’s visual language had entered a new phase — less graffiti, more digital x-ray. The sleeve felt like evidence seized from a surveillance state, cold and clinical, as if even the artwork were under interrogation.

Reception was divided. Some critics hailed it as a masterpiece of minimalism, a logical continuation of the band’s evolution into harsher, more abstract territory. Others found it too bleak, too detached, missing the soulful warmth that defined Blue Lines and Protection. But with time, 100th Window has been reassessed as one of Del Naja’s boldest artistic statements: a record that strips music down to architecture, exposing its beams and shadows without compromise.

Mezzanine was the dark bloom, 100th Window was the fallout — a cold architecture built from fracture, paranoia, and precision. It stands as proof that Del Naja was no longer just a member of a band. He was architect-in-chief, turning Massive Attack into a total artwork where music, image, and ideology fused into one uncompromising system.

Toward Heligoland: 2003–2010

The seven years between 100th Window and Heligoland were not silence — they were incubation. Massive Attack’s sound had reached an icy minimalism in 2003, but the years that followed saw Robert Del Naja rebalancing the equation, drawing in new voices, and broadening his canvas until it was wide enough to hold an entirely different atmosphere.

One crucial return was Daddy G. After stepping back during 100th Window, his reappearance restored a counterweight: groove, warmth, and a deep soul sensibility that offset Del Naja’s precision. The balance between the two became the tension that defines Heligoland — cold fire and warm smoke, inhabiting the same frame.

Del Naja also deepened his partnership with Neil Davidge during this period, moving beyond band work into cinema. Together they scored films like Bullet Boy (2004) and Danny the Dog (Unleashed, 2005), projects that demanded music behave like atmosphere, shaping not just scenes but psychology. Scoring film expanded Del Naja’s sense of how sound and image converse, a lesson that would ripple through the widescreen feel of Heligoland.

In 2006, Massive Attack released Collected, a retrospective that didn’t just revisit old ground but added new material and remixes. Around the same time, Del Naja’s curatorial instincts sharpened through DJ sets and mixtapes that pulled in textures from minimal techno, indie rock, and global electronica. He was learning to orchestrate entire constellations of sound.

The band also began carefully assembling an expanded roster of collaborators. Damon Albarn, Martina Topley-Bird, Hope Sandoval, Tunde Adebimpe, and Guy Garvey — each voice was chosen like a color on a palette, not for name recognition but for texture. This was no casual guestlist; it was Del Naja building an ensemble to give Heligoland its spectrum.

Visually, his art entered a new phase. The stencil roots were still there, but they bloomed into bold, portrait-driven canvases: faces against fields of vivid orange, red, and green, sometimes haloed by surreal arcs of color. The Heligoland artwork was already germinating in his studio years before the album’s release, a continuation of his project to make music and image inseparable.

And around all of this was the world itself. Post-9/11 paranoia, the Iraq War, the expansion of surveillance states — the themes that had made 100th Window so cold were still present, but Del Naja’s response shifted. Rather than freeze, the new work sought to bloom. Rather than reduce, it layered. Rather than retreat, it invited others in. That impulse — expansive, collaborative, painterly — is what made Heligoland possible.

Heligoland: Constellations in Color

By 2010, Massive Attack had already reshaped music twice: first with the warm hybridity of Blue Lines, then with the dark rupture of Mezzanine and the cold precision of 100th Window. Heligoland was about expansion — a collaborative bloom that pulled new voices into its orbit and painted the Massive Attack universe in more vivid tones than ever before.

The lineup of collaborators reads like a manifesto of textures. Damon Albarn brought his restless melodic intuition to Saturday Come Slow. Hope Sandoval of Mazzy Star turned Paradise Circus into a hymn of fragile seduction, her voice floating like cigarette smoke in slow motion. TV on the Radio’s Tunde Adebimpe lent Pray for Rain a surreal elasticity, stretching syllables until they bent around the beat. Guy Garvey of Elbow delivered Flat of the Blade with bruised intimacy, while Martina Topley-Bird’s presence stitched the album together like connective tissue. And Horace Andy — eternal anchor, eternal prophet — returned once more, grounding Girl I Love You in the voice of scripture.

The sound was warmer, more human, yet still uneasy. Beats felt less like machines and more like breathing. Pianos and guitars folded into electronics with painterly care, every texture placed as if on canvas. Heligoland was mural: layered, colorful, luminous even in its shadows. It was Massive Attack proving that darkness could hold light, and paranoia could coexist with beauty.

The title itself is telling. Heligoland is a tiny German archipelago in the North Sea, historically a site of shifting sovereignties, bombings, and resettlements. It is a place defined by borders and transformations — exactly the kind of metaphor that suited Del Naja’s project. The album feels like a landscape battered by history but still standing, radiant and strange.

Visually, Del Naja’s artwork was as essential as the music. Gone were the monochrome beetles and CCTV fragments of the Mezzanine era. In their place: bold stencil portraits against saturated fields of color, punctuated by surreal arcs — rainbows sliced into circles, halos reimagined as design motifs. The most iconic image, a stark black-and-white face on a field of orange crowned by a rainbow arc, felt at once devotional and defiant. It was graffiti’s urgency evolved into painterly iconography, a sign that Del Naja’s visual art had entered its own prime.

Critics praised Heligoland for its ambition and its range, though its quieter power meant it didn’t explode into the zeitgeist like Mezzanine. For some listeners, however, it has grown into the most resonant of all Massive Attack’s works: the one that balances menace with melody, despair with beauty, austerity with color. In hindsight, it feels like the band’s most generous record — a constellation of collaborators shining in the same sky.

Legacy has only deepened its importance. Heligoland proved that Massive Attack was not a band frozen in the paranoia of 100th Window or the shadows of Mezzanine. It was a living art collective, capable of reinventing itself without losing its identity. And at the center, once again, was Robert Del Naja: curator, painter, architect of atmospheres, orchestrating not just songs but entire worlds.

Other Instruments: Experiments & Innovations

After Heligoland, Robert Del Naja’s creative energy spilled far beyond the traditional frame of “band” or “album.” For him, Massive Attack had always been more than music — it was a laboratory where sound, image, and politics fused. Between 2010 and 2016, that laboratory began to take on new forms, bending technology and biology into instruments no one else was building.

Fantom was the first of these. Launched in 2016 but prototyped earlier, the app reimagined how music could exist in the digital age. Instead of playing fixed tracks, Fantom remixed Massive Attack material in real time, responding to a user’s environment: their movement, their location, even their heart rate and camera input. Each listen was unique, ephemeral, and unrepeatable. For Del Naja, this was the logical extension of sampling culture: the listener becomes the sampler, the body becomes the sequencer.

Meanwhile, the band’s live shows became sites of visual and political experimentation. Collaborations with United Visual Artists (UVA) escalated into Present Shock, an ongoing series where newsfeeds, statistics, and algorithmic headlines were woven directly into the stage design. A Massive Attack concert was no longer just performance — it was real-time media criticism, turning data into architecture, and headlines into thunder. The spectacle wasn’t distraction; it was confrontation.

Del Naja also pushed into gallery territory with canvases and installations that extended his graffiti language into archival form. Faces fractured into xerox scars, surveillance motifs collided with propaganda imagery, and digital static became painterly texture. His visual practice was no longer the shadow side of the band — it was a parallel body of work, documented in the volume 3D & the Art of Massive Attack. The book made clear that what the world had seen as “album covers” were actually fragments of a much larger visual archive, alive in both street and studio.

This period was less about traditional output and more about building systems. Music became code, stage design became journalism, and paintings became archives. Massive Attack was mutating again, not into another genre but into another form — one where art and activism blurred into a single operating system. And at the center of this mutation was Del Naja, treating every new tool — sampler, screen, algorithm, spray can — as another instrument in the arsenal.

Ritual Spirit EP: Cinematic Resurrection

In January 2016, Massive Attack returned with Ritual Spirit, a four-track EP that proved they were still capable of reinvention. Short in runtime but immense in impact, it fused old alliances with new blood, and once again blurred the boundaries between music, cinema, and conceptual art. Produced by Robert Del Naja with Euan Dickinson, it carried the DNA of the band’s past while pointing unmistakably forward.

The EP opened with Take It There, a reunion with Tricky that felt like a full-circle moment. His cryptic, mercurial flow wound through Del Naja’s shadowy production like a voice returning to its birthplace. Dead Editors brought in Roots Manuva, delivering dense bars over fractured beats — a reminder that Massive Attack had always been fluent in hip hop’s language but spoke it in their own strange accent. Azekel’s turn on the title track added a smoother, soulful edge, a lighter texture against the EP’s heavier shadows.

The most explosive moment came with Voodoo in My Blood, featuring Young Fathers. The track itself is a kinetic charge — urgent, snarling, driven by voices that seem to argue and agree all at once. Its video, directed by Ringan Ledwidge, is one of the most unforgettable works in the Massive Attack canon. Starring Rosamund Pike, it stages an uncanny encounter in an underground passage: a lone woman confronted by a floating metallic orb. What begins as curiosity turns to possession as the orb drills into her eyeball, sending her into a convulsive dance of fear and surrender. The piece plays like psychological sci-fi horror, evoking Cronenberg as much as Kubrick. It’s a parable of technology, control, and vulnerability.

Ritual Spirit wasn’t a full album, but it was proof of life — and proof that Robert Del Naja was still thinking cinematically, still bending the music video form into something closer to short film. The EP blurred boundaries once again: music as code, videos as cinema, sound as system. For a band more than two decades into their career, this was a resurrection.

The Spoils & Come Near Me

Later in 2016, Massive Attack extended this return with two standalone singles: The Spoils (featuring Hope Sandoval) and Come Near Me (featuring Ghostpoet). If the Ritual Spirit EP was the resurrection, these singles were its haunting after images — each accompanied by a video that ranks among the most powerful in Massive Attack’s canon.

The Spoils, directed by John Hillcoat and featuring Cate Blanchett, slowly transforms her face into sculpture. The song itself, with Sandoval’s spectral vocal, already feels like memory dissolving in slow motion. Paired with the imagery, it becomes a meditation on identity, celebrity, and time itself. Watching Blanchett’s familiar features turn into abstract texture is both haunting and strangely serene. It suggests that beauty is fragile, but also that every image we worship will eventually decay into dust. As always with Del Naja, the visual wasn’t illustration but extension — a way of showing the song’s soul through another medium.

Come Near Me, directed by Ed Morris, completes this cycle with a minimalist but devastating concept. The entire video is a single continuous shot: a woman walking backwards as a man follows, the space between them charged with tension. No effects, just choreography and gravity. The further she retreats, the more inevitable the ending feels, until she finally backs into the ocean to her inevitable demise. The track itself, featuring Ghostpoet, is hypnotic and understated, its slow-motion pulse echoing the inexorable pull between the two figures. In its simplicity, the video achieves something profound: a portrait of love, pursuit, and separation rendered as pure movement through space.

Together, these singles confirmed that Massive Attack were still pushing the boundaries of what a “music video” could be — cinematic artworks, each expanding the songs into sculptural, choreographic, and psychological territory. More than two decades after Blue Lines, Del Naja and Massive Attack were still reinventing the grammar of music itself.

Politics in the Bassline

For all the atmospheres and aesthetics, Robert Del Naja’s work has always carried a political charge. Massive Attack was never just background music; it was protest disguised as beauty, critique hidden in bass. Over the past decade, that current has become explicit. Del Naja has turned the band into a platform for activism, building art that doesn’t just reflect the world but seeks to rewire it.

In 2013, Del Naja collaborated with Thom Yorke and Euan Dickinson on the score for The UK Gold, a documentary exposing Britain’s role as a global hub for tax avoidance and financial corruption. The soundtrack was stark, restless, and unnerving — a sonic mirror of systemic rot. For Del Naja, it was another way to weaponize music: not entertainment, but evidence.

During the 2020 lockdown, when touring was impossible and isolation was the global condition, Massive Attack released Eutopia — a three-track audiovisual manifesto created with Young Fathers, Algiers, and Saul Williams. Each track paired music with monologues from thinkers like Christiana Figueres (climate action), Gabriel Zucman (tax justice), and Guy Standing (universal basic income). The visuals, generated by AI, dissolved faces into shifting digital textures, underscoring the fragility of identity in the data age. This wasn’t an EP in the traditional sense; it was a manifesto disguised as art, insisting that new systems are possible even in crisis.

Del Naja’s activism has also turned inward, interrogating the very industry that sustains him. In 2021, Massive Attack commissioned the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research to model the carbon footprint of live touring. The report became the foundation for Act 1.5, a groundbreaking 2024 Bristol show designed as a proof of concept for low-carbon live music. Solar power, battery storage, circular stage design, local supply chains — every detail was a statement. The show wasn’t just a gig; it was a prototype for a future where culture doesn’t cost the earth.

From The UK Gold to Eutopia to Act 1.5, Del Naja has reframed what it means to be a musician in the 21st century. His basslines have always carried menace, but now they carry manifestos. The message is clear: art cannot be neutral in an age of crisis. It must resist, expose, and re-imagine. And Robert Del Naja has made Massive Attack the vessel for that resistance.

The Banksy Question

No portrait of Robert Del Naja can avoid the rumor: that he is, in fact, Banksy. The theory has circulated for years, fueled by coincidences of timing and geography, by their shared Bristol origins, by the stencil scars that mark both of their works. In 2016, Scottish journalist Craig Williams published an investigation that superimposed Banksy’s known murals over Massive Attack’s tour history. Again and again, a pattern emerged: a new work by Banksy appearing in a city just as Massive Attack played there. The conclusion seemed irresistible: the frontman of Massive Attack was also the world’s most famous anonymous artist.

The speculation was only amplified by Del Naja’s appearance in Banksy’s own film, Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010). Cloaked in shadow, speaking with authority about the graffiti underground, he became both participant and witness in a movie that blurred reality and myth. His presence in that context felt like a wink — evidence to some, misdirection to others, but always fuel for the fire.

Del Naja has denied the theory repeatedly, sometimes laughing, sometimes deflecting, sometimes leaning into the ambiguity. And the truth is, whether he is Banksy or not almost doesn’t matter. What matters is why the myth resonates: because we live in a culture addicted to single-genius narratives, desperate to put a name and a face to what is often the work of networks, collectives, and communities. To believe that one man could simultaneously lead Massive Attack and orchestrate Banksy’s global interventions is to misunderstand the very spirit of both projects. They are less about solitary authorship than about systems of collaboration and disruption.

Still, the rumor lingers, in part because it feels right. Del Naja could be Banksy — his hands, after all, are already in music, painting, politics, technology, and the streets. The suspicion is a kind of compliment: a recognition that he embodies the same spirit of insurgent creativity, of art as sabotage, of imagery as weapon. Whether or not the mask fits, the myth itself is telling. It confirms that Robert Del Naja has become something larger than a single discipline or medium. He is a figure we struggle to pin down, precisely because his work refuses the comfort of a single identity.

Conclusion: Embers Into Fire

Robert Del Naja’s career resists neat summary because it was never built for neatness. From the spray cans of Bristol to the basslines of Mezzanine, from DNA-encoded albums to carbon-neutral concerts, his work has always lived in the slipstream between art forms. He is not just a musician, or a painter, or a provocateur. He is a systems thinker, an activist, a trickster with a stencil and a subwoofer — forever asking how creativity can bend the rules of the world around it.

In the foreword, we remembered the first shiver of Unfinished Sympathy, the shock of the Teardrop fetus, the slow burn of Heligoland. Those encounters were not accidents. They were designed experiences — atmospheres carefully built to enter the bloodstream and never leave. That’s the secret of Del Naja’s art: it lingers. It embeds itself like code in the body, like graffiti on the wall, like a protest chant echoing long after the crowd disperses.

At RIOT, we recognize that impulse because it drives us too. Like Massive Attack, we are not content to decorate culture; we want to rewire it. To treat creativity not as an accessory but as an engine. To prove that design, storytelling, and technology can be insurgent forces, capable of reshaping industries and imaginations alike. The bassline may be different, but the philosophy is kin.

Robert Del Naja shows us that art can be weapon, archive, prophecy, and refuge all at once. He shows us that the role of the artist is not to soothe but to unsettle, not to obey but to disrupt. And he reminds us — as he always has — that the embers of an idea, if tended, can set the whole room on fire.