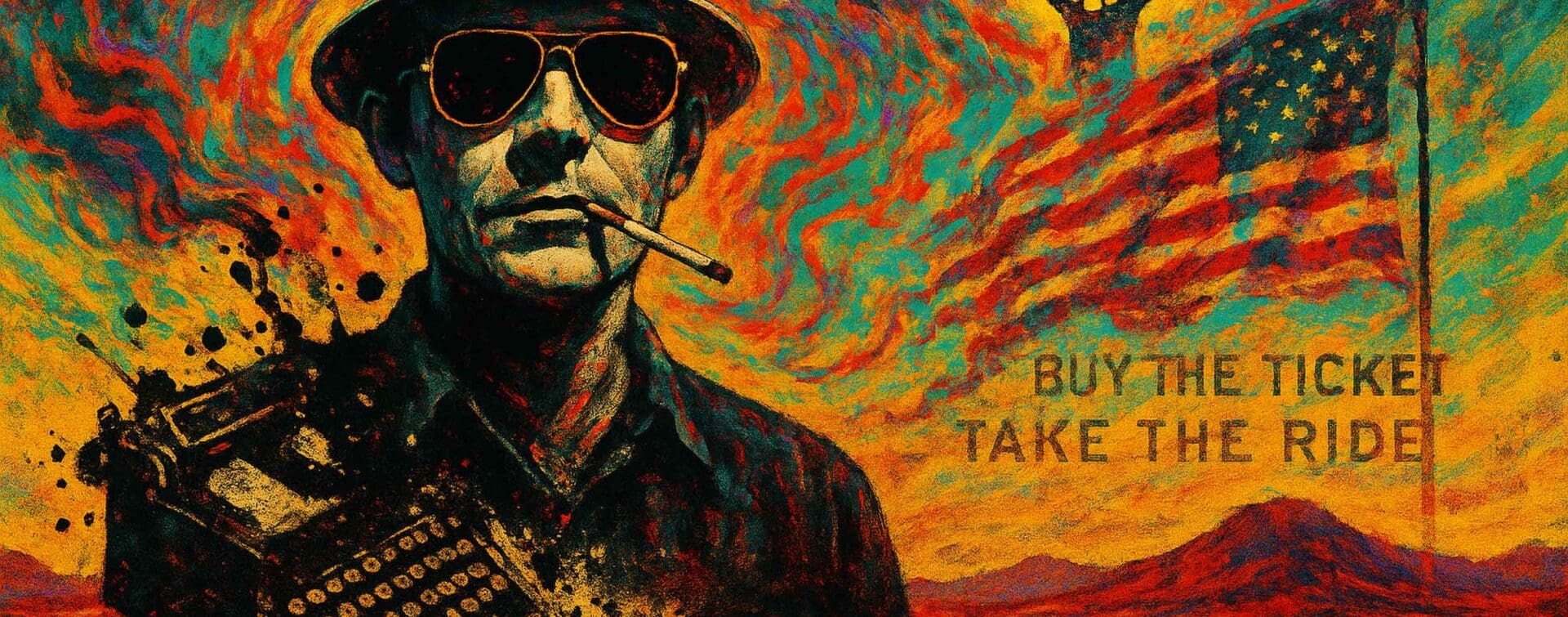

A Typewriter Is a Loaded Gun: The Gospel of Hunter S. Thompson

The Gospel of Hunter S. Thompson

Somewhere between the American Dream and the American Nightmare, a man lit a cigarette, loaded a page, and pulled the trigger. What came out was Gonzo.

Hunter S. Thompson came barrelling through the gates of 20th-century media like a drunk angel with a grudge, clutching a cigarette holder, a .44 Magnum, and a head full of better questions. And in his wake? Wreckage. Reverence. The blueprint for how to tell the truth in a world that punishes truth.

This is not a biography or a tribute. It is a séance in six acts. A RIOT disguised as a reading. A love letter written in Sharpie on the inside of a speeding convertible, heading west with the trunk full of amphetamines and unfinished business.

If God is in the details, then Thompson was the devil’s court stenographer — banging out scripture on a Selectric, high on ink and vengeance, while the world looked away.

“The Edge… there is no honest way to explain it, because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over.”

— Hunter S. Thompson

Welcome to Bat Country

Las Vegas wasn’t the beginning. But it was the flashpoint. The scene of the crime. The cathedral of decay where Hunter S. Thompson rolled a rental car into the heart of the American psyche and left it rotting behind a neon grin.

There was no story. That was the story. No assignment — just two men, as high as the national debt, chasing mirages through casinos and sandstorms. One of them thin, twitchy, and possessed by syntax; the other a human avalanche in mirrored sunglasses, looking like God’s lawyer on a bender. Together, they weren’t covering culture — they were crucifying it.

And yet, out of that wreckage came Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a book that reads like a hallucinated eulogy. Not for a city, but for a country. For an era. For the myth of forward motion. It was journalism turned inside out — a memoir wearing a disguise, a bad trip with footnotes, a howling requiem that somehow managed to be funny in the exact way dying is funny if you watch it through the right kind of glass.

This was the birth of a new kind of storytelling — one that didn’t apologize for subjectivity but made it sacred. Thompson didn’t want to show you what happened. He wanted you to feel what it did to him. He made the reader complicit. A passenger. A witness. Blood on your hands, ink on your teeth.

“We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold…”

It’s not just an opening line. It’s an incantation. A line of demarcation between everything you thought reporting was — and whatever this beautiful, burning thing would become. Gonzo wasn’t born in Vegas, but it sure as hell found its teeth there.

The Birth of Gonzo

May 1970. Churchill Downs. The most decadent weekend in southern sport. Hunter S. Thompson shows up to cover the Kentucky Derby and winds up documenting the death of American grace. He doesn’t write about horses. He writes about hats. About vomit. About bourbon-soaked businessmen leering at debutantes like wolves at a zoo. The sport is just a backdrop. The story is the rot.

He turns in something wild. Unhinged. Ravaged by honesty. The editors blink. Bill Cardoso reads it and grins: “This is pure Gonzo.” And with that, a genre is born. Not from theory. From impact.

Gonzo journalism wasn’t a new style. It was a mutiny. A declaration that the writer was no longer a fly on the wall — they were the wall bleeding, the glass shattering, the room catching fire. Gonzo says: tell the truth as it happens to you. Filter the facts through your bloodstream. Weaponize your subjectivity. Make your trauma sing.

“Objective journalism is one of the main reasons that American politics has been allowed to be so corrupt for so long.”

That story — “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” — changed everything. Not just for Thompson. For journalism. For storytelling. For every filmmaker, artist, copywriter, and cultural saboteur who’s ever realized that neutrality is a kind of lie.

It wasn’t a report. It was a fever dream. A drunken sermon. A design — written to infect. Which is exactly what we believe in at RIOT. You want to tell the truth? You better get dirty. You better mean it.

Hell’s Angels & the Baptism of Proximity

Before Vegas, before the Derby, before the myth metastasized — there was a man, a motorcycle gang, and a year of brutal proximity. In 1965, Hunter S. Thompson embedded himself with the Hell’s Angels. Not for a weekend. Not for a feature. For a year. He rode with them. Drank with them. Slept near their dogs. Took punches. Earned scars. And came back with a manuscript that read like it had been clawed out of asphalt.

Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga wasn’t journalism. It was anthropology with blood in its teeth. A story told from the inside out — no gloss, no distance, no safety net. And in that chaos, Thompson found the foundation of his method: you don’t observe the story — you survive it.

He watched the Angels drift across counties like feral myths, and talk politics like Shakespeare on trucker speed. He recorded it all. Not with polite detachment, but with a kind of engaged fearlessness. Then, near the end, they turned on him. Sent him limping back to the typewriter with his ribs bruised and his method baptized.

“In a closed society where everybody’s guilty, the only crime is getting caught. In a world of thieves, the only final sin is stupidity.”

This was Thompson’s first crucible. It proved that his writing didn’t work at arm’s length. It had to be lived. The cost of that decision would haunt his entire career — physically, spiritually, financially. But it also made the work radioactive with truth. You can’t fake contact. You can’t Google the fear out of a parking lot full of bikers and beer bottles and half a dozen engines snarling like war machines.

And here’s the parallel: at RIOT, we don’t pitch from the sidelines. We embed. Whether it’s subcultures, brands, stories, or visions — we move from inside the pulse. The only way to make something that feels real is to let it mark you. Thompson knew that. We live it.

Freak Power: How to Design a Revolution

By 1970, Hunter wasn’t just writing the American collapse — he was running for office in the middle of it. Sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado. The campaign wasn’t a prank. It was a plan. A hostile takeover of civic aesthetics. A full-spectrum disruption of how politics looked, sounded, and sold itself to the public.

The manifesto read like a design doc from the future: disarm the police, rename Aspen “Fat City” to repel greedy developers, outlaw the land rapists, legalize drugs (not as hedonism but harm reduction). It was part performance, part prophecy. And it nearly worked.

But it wasn’t just policy. It was the identity system: black-and-white posters by Thomas W. Benton, featuring a double-thumbed Gonzo fist clutching a peyote button — a symbol so striking it survived the campaign and became the eternal sigil of the movement. Branding not as decoration, but as battle flag.

“We cannot expect people to have respect for law and order until we teach respect to those we have entrusted to enforce those laws.”

Thompson shaved his head so he could call his crew-cut opponent “my long-haired adversary.” He flipped the optics. Weaponized absurdity. Used humor as a scalpel. The entire campaign was a masterclass in visual sabotage — and it scared the hell out of the establishment.

This is where the creative lesson detonates: identity is power. Design is not decoration. It is position. And at RIOT, we treat every brand, every frame, every campaign like a movement in waiting. When the symbols are right, the story doesn’t have to beg — it leads.

The Mojo Wire and the Machinery of Madness

By 1972, the circus was fully operational. Nixon was running for re-election. McGovern was surging. And Rolling Stone handed Thompson a backstage pass to American collapse. The result was Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 — a masterpiece of political coverage disguised as a bad acid trip.

It wasn’t “journalism.” It was telepathy with collateral damage. He invented new speeds for reporting. The pieces were written at 3AM, high on adrenaline and rage, faxed over wires that hissed like vipers. He called it the Mojo Wire — a late-night channel between his brainstem and the masses. A sacred fire that couldn’t be tamed or edited. Only survived.

The Nixon he painted wasn’t a man — it was a myth, a disease, a sickness in the body politic. Thompson saw it all before we had the language for it. The smirk behind the mask. The algorithm of evil. And he wrote like someone whose house was already burning.

“Some people will say that words like “scum” and “rotten” are wrong for objective Journalism.”

What Hunter S. Thompson created was a creative resistance. He broke the form to show its cracks. He told the truth by distorting reality just enough to make it visible. And through the Mojo Wire, he made journalism feel dangerous again — like it could still knock down walls, wreck illusions, name the beast.

At RIOT, we know this rhythm. That frantic creative frequency. That live-wire feeling when the deadline is a loaded gun and the brief is a Molotov. We know how to make a RIOT — because we believe the best stories aren’t just observed. They’re thrown like bricks.

Hunter’s Creative Ethos: A Field Guide for the Mad

Under the bourbon, beneath the bravado, behind the blur — Hunter S. Thompson was a craftsman. A brutal one. The kind that rewrote until the language bled right. The kind that understood you can’t write like that unless you feel like that. He wasn’t chasing chaos. He was wrestling form.

So what do we take from the Doctor of Gonzo? What’s the toolkit for makers who want to light something on fire and still call it art?

1. Write like it costs you something

Hunter filed open wounds. That’s the price. No posturing. No half-truths. If it doesn’t come from the gut, don’t bother printing it. The work has to feel dangerous. Or it’s dead.

2. Design your myth

Freak Power wasn’t just a sheriff campaign. It was a brand, a movement, a spectacle. Thompson understood that ideas need shape to survive. Symbols. Slogans. Visuals that stick to the psyche. The double-thumbed fist didn’t ask for attention — it took it.

3. Kill the myth when it stops serving you

He never stopped dismantling his own persona. The drugs. The cartoon. The iconography. He tried to outrun it because he knew the packaging can kill the prophet. Don’t believe your own bio. Burn it and start again.

4. Enter the frame

Gonzo means the subject doesn’t sit safely behind the camera. The camera blinks. The subject walks in. Be the story. Risk the fallout. If it doesn’t mark you, you didn’t get close enough.

5. Treat style like a weapon, not a costume

Style without intent is just noise. Hunter’s voice was operatic because it was earned. Every strange turn of phrase, every rant, every hallucinogenic aside — it all served the same god: truth.

6. Make the edit the altar

The final draft is where the gospel lives. Thompson’s “sloppy” energy was carefully engineered. He edited like a butcher — carving muscle, tossing fat, leaving only what roared. Never confuse mess for meaning. Earn the chaos in post.

7. Tell the truth like it could get you killed

Because in some corners of culture, it still can. And in the ones where it can’t? That’s where it matters most.

At RIOT, we carry this fire. We make with intent. We write like the page is flammable. We design like meaning still matters. And we believe that the only work worth putting into the world is the kind that wakes people the fuck up.

Hunter’s not just a ghost in our journal. He’s a North Star. A dirty mirror.

Legacy in the Fire: Why Hunter Still Matters

Hunter S. Thompson didn’t leave behind a body of work. He left behind a scorched terrain where language refused to obey the rules, and truth wore brass knuckles. He didn’t just tell the story — he wrestled it to the ground and made it confess.

He matters now more than ever. Because we’re drowning in fake neutrality. In clean, empty paragraphs. In creative that’s been stripped of its teeth to fit a brand tone guide. Because too many stories are “safe,” and too much design is decoration. Because we’re being fed content instead of confrontation.

But the fire’s still here. Still burning under the surface. In every writer who gives a damn. In every filmmaker who refuses polish. In every designer who knows that meaning beats metrics. Hunter lit that fire. Our job is to keep it fed.

“It never got weird enough for me.”

At RIOT, we’re not chasing algorithms. We’re chasing impact. We treat every story like it might be the last one that gets heard. We design with risk. We write with voltage. We film like we’re trying to haunt people — in the best possible way.

Because that’s what Hunter taught us:

You don’t create to be liked.

You create to be felt.

And if the typewriter’s still loaded — you fire.