Ads That Changed Everything: The Weirdest, Wildest, Most Surreal TV Commercials

30 Seconds to Immortality

Advertising’s always had an image problem.

At its worst, it interrupts. At its best? It interrupts everything — expectation, genre, even culture itself.

That’s what the most iconic TV commercials do: they short-circuit reality and sell you something unforgettable.

This isn’t a list of the most awarded.

Or the most viewed.

This is something more human.

These are the commercials that moved us. That broke something. That rewired creative culture by being bolder, weirder, smarter, funnier, and more emotionally precise than anyone had any right to expect from thirty seconds wedged between reruns and reality TV.

Some feel like short films.

Some feel like fever dreams.

Some feel like truth in a language only commercials speak.

We’ve split them by tone, not timeline. By impact, not industry platitudes. Because the best ads — the ones that live rent-free in our heads decades later — they don’t belong to a format. They invent their own genre.

This isn’t just a retrospective.

It’s a remix.

A mixtape.

A love letter.

A creative survival guide for anyone who gives a damn about making something unforgettable.

And because this is the first installment of Ads That Changed Everything, we’re starting where advertising gets the strangest. Not with the polished “greatest hits,” but with the surreal. The anarchic. The fever dreams that somehow sold mints and chocolate bars while rewiring what TV could feel like.

This volume is about weird that worked. Ads that broke logic, broke rules, but stuck, because they had the courage to be absurd and the craft to land it.

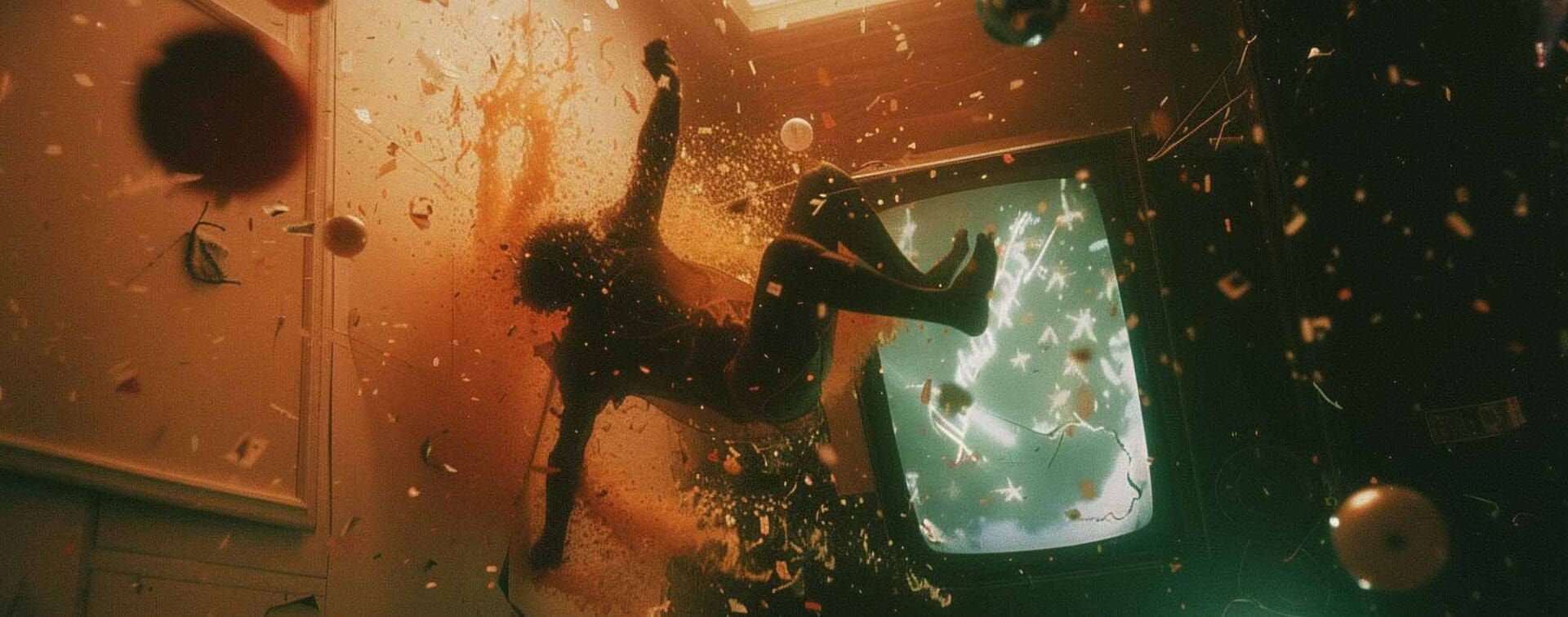

ABSURDIST BRILLIANCE: The WTFs That Worked

Some ads tell stories.

These ones are surreal, stupid, beautiful, brilliant. They shouldn’t work — but they do. Not because they’re random, but because they’re rooted in something precise: a product truth, a feeling, a brand unafraid to get weird.

These are the ads that got banned. The ones you couldn’t stop quoting. The ones that made your parents ask, “what the hell was that?” — and made you fall in love with advertising anyway.

This is the art of the unexpected. Absurdism as strategy.

And we begin with the orange slap that started it all for us.

Tango – “You Know When You’ve Been Tango’d” (1992)

Advertising Agency: HHCL & Partners

“You know when you’ve been Tango’d.”

It starts like a normal ad: three lads standing outside a corner shop. One of them cracks open a can of orange Tango and takes a long sip. There’s a moment of silence. Then we hear it — a sports commentator’s voice, cutting in as if we’ve just entered Match of the Day.

“Hello Tony, I think we might use a video replay here…”

Suddenly, we’re in a sports broadcast. The footage rewinds, the sip replays… and now we see what we missed the first time: an orange-painted man, nearly naked and totally serious, dashes into frame, slaps the drinker full in the face with two hands, and disappears. The slap echoes like a shotgun. The drinker rocks back, dazed.

It’s deranged. It’s brilliant. And it was banned almost immediately.

Kids across the UK started reenacting the slap at school. Teachers panicked. Headlines followed. The Independent called it “dangerously influential.” The ASA pulled it from rotation.

Which, of course, only cemented its place in advertising legend.

The genius isn’t just the slap — it’s the way the whole ad is structured like a sketch. First, the set-up: a normal scene outside a shop. Then the commentary: familiar, British, authoritative. Then the replay: a reveal of absurdity hiding in plain sight. And finally, the punchline: a single line so quotable it burned itself into playground folklore.

This was absurdism disguised as normalcy. Not surreal for its own sake — but structured like a sketch, directed like a football replay, and delivered with the confidence of a brand that knew weird was its weapon.

“You know when you’ve been Tango’d” didn’t explain anything. It didn’t have to. It trusted the viewer to get the joke — and when they did, they owned it.

At RIOT, we talk about creative bravery — but this was weaponised British surrealism. A slap that became a slogan. An advert that hijacked the format to create folklore.

Tango ambushed culture with this one!

Cadbury – “Gorilla” (2007)

Advertising Agency: Fallon London

“A glass and a half full of joy.”

The camera glides slowly across a purple wall. We see a snare drum. Cymbals. A deep breath. And then… a gorilla.

He’s sitting behind a drum kit. Alone. The room is silent. Then the music begins — Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight” — soft, eerie, iconic. The gorilla closes his eyes. He’s feeling it.

There’s no smiling families. No children with milk moustaches. Just tension. Timing. Anticipation. The gorilla waits.

Then — the fill.

You know the one. The most air-drummed moment in pop history. The gorilla explodes into motion, pounding the kit like he’s been waiting his whole life for this beat.

And only then — at the very end — the screen fades to purple. The Cadbury chocolate bar appears alongside a single line: “A glass and a half full of joy.”

No voiceover. Just a feeling. Because that was the brief: “get the love back.”

Cadbury had lost its shine. A salmonella scare. Declining affection. Fallon could’ve played it safe — comfort messaging, nostalgia, product benefits. But instead, they made a gorilla play the drums to Phil Collins and trusted the public to feel the connection.

And we did.

This was branded entertainment before anyone called it that. A TV spot that functioned like a short film — strange, funny, hypnotic — with just enough confidence to keep the product in the wings until the applause.

And part of what made it unforgettable was the question nobody could answer: “How did they do it?”

Was it CGI? Puppetry? A real gorilla? A man in a suit?

The execution was so surreal and so precise that the line between creature and performance blurred. People wanted to know. Which meant they kept watching. Kept talking. Kept loving it.

Because when the craft becomes part of the conversation, the ad becomes more than an ad. It becomes culture. These aren’t just ads — they’re iconic TV commercials that shaped how we think about storytelling, strategy, and spectacle.

Trebor Softmints – “Mr Soft” (1987)

Advertising Agency: Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB)

“Mr Soft, won’t you tell me why the world in which you’re living is so strange… how come everything around you is so soft and rearranged?”

Mr Soft doesn’t walk — he drifts. Limbs loose, eyes half-closed, moving like a puppet suspended underwater. He glides through a high street where nothing behaves the way it should. Cars wobble. Postboxes bend. Even gravity seems optional.

The world sways in time with a reworked version of Steve Harley’s “Mr Soft” — the familiar tune made stranger, dreamier, as though warped by heat. The lyrics echo the visuals: “Why is everything around you so soft and rearranged?” In this universe, the answer is simple: because Mr Soft is here.

He hands out Softmints as he moves — to parking meters, to postboxes — and they chew, obediently, impossibly. It’s absurd, but consistent. A soft logic.

And then it breaks.

At the very end, Mr Soft drifts into a lamppost that doesn’t yield. No wobble, no bend. Just a solid hit. He crumples, a marionette with strings cut, as the dream glitches.

“Bite through the shell of a Trebor Spearmint Softmint and everything turns chewy and soft. They’re crispy on the outside, chewy on the inside.”

That voiceover lands like an answer. The surreal world wasn’t random — it was metaphor. The city bent and swayed because the mints do too. Hard shell, soft heart. The lamppost gag makes it human, but the line makes it make sense.

That’s why Mr Soft works. It isn’t just weird for weird’s sake. It’s a commitment to a single idea — softness — explored with charm, song, slapstick, and a twist of British surrealism. The strangeness pulls you in, the tagline ties it down, and decades later, people still hum the jingle.

Sony Bravia – “Balls” (2005)

Advertising Agency: Fallon London

“Colour. Like no other.”

The ad opens on a San Francisco street at dawn. It’s quiet, empty. Then — a single ball bounces. Then another. And another. Until suddenly the entire city is alive with colour, 250,000 balls flooding down the hill in a shimmering tide of chaos.

No CGI. No trickery. Just a quarter million hand-released bouncy balls, captured by two dozen cameras, tumbling and ricocheting through the real world. A rainbow unchained.

Set to José González’s haunting cover of “Heartbeats,” the effect is hypnotic. Chaos and calm held together in perfect balance. Each frame could be a painting. Each bounce feels like the product promise made real: colour, like no other.

And then there was the behind-the-scenes film — which revealed the insane logistics: streets closed for days, leaf blowers to corral the balls, teams of locals sweeping them into place. The production became part of the legend. Proof that sometimes the most surreal ideas work best when they’re done for real.

What makes “Balls” unforgettable isn’t just the spectacle, or even the music. It’s the restraint. No hard sell. No features list. Just a feeling: the way colour should move. A brand idea expressed not as words, but as physics.

For years afterwards, every art director in the world referenced it. Every pitch deck carried echoes of it. It wasn’t just a commercial — it was proof that if you commit to beauty at scale, people will stop, watch, and remember.

Budweiser – “Frogs” (1995)

Advertising Agency: DDB Worldwide

“Bud… Weis… Er.”

It’s night. A swamp. The camera lingers on the still water, the kind of scene you’d expect from a nature doc. Then: a croak. Low, guttural. “Bud.” A second frog joins: “Weis.” A third completes it: “Er.”

That’s it. That’s the whole ad. Three frogs on lily pads, croaking a beer brand into existence.

It shouldn’t work. It’s too slow, too strange, too stupid. And yet, it’s unforgettable. Within weeks of airing during the Super Bowl, the frogs were everywhere. Merch, parodies, late-night jokes. “Bud–Weis–Er” became a playground chant, an office gag, a cultural echo.

Part of its genius was timing. In an era when beer ads leaned hard on macho humour, bikini babes, and sports clichés, Budweiser dropped an ad that said almost nothing — and still said it all. The frogs didn’t tell you how the beer tasted. They just made the name impossible to forget.

The absurdity was the strategy. By leaning into repetition and surreal minimalism, Budweiser made itself not just memorable, but quotable. You couldn’t parody it without repeating the brand. You couldn’t talk about it without croaking the name.

That’s why it changed the game. It proved that sometimes the dumbest idea in the room is the smartest move a brand can make.

Budweiser – “Whassup?!” (1999)

Advertising Agency: DDB Chicago

“Whaaaaaassssuuuuuup?!”

It opens plain, almost boring. A man answers the phone: “What’s up, B?”

“Nothing. Just watching the game, having a Bud.” It’s everyday stuff — familiar, ordinary, forgettable. Until the first “Whassup?!” lands. Stretched out, playful. Then echoed back. Then echoed again. Each friend on the call stretches it further, louder, sillier, until the whole thing collapses into laughter.

That was the genius. The absurdity didn’t come from nowhere — it built out of the mundane. The script grounded itself in normal life (guys, game, beer) and then pushed repetition until it tipped into chaos. It made the ridiculous feel real, because it started real.

The reason it rang so true is because it was true. “Whassup?!” wasn’t born in a brainstorm — it came from True, a short film by Charles Stone III, where he and his real friends riffed the same way. DDB Chicago spotted it, licensed it, and invited Stone to direct the Budweiser version with the same cast. Which meant what you saw on screen wasn’t acting. It was a ritual captured and repeated — friendship, distilled into a catchphrase.

The effect was immediate. The night it aired during Monday Night Football, “Whassup?!” started spreading. By the Super Bowl, it was everywhere. Offices. Schools. Talk shows. SNL sketches. Parodies in every language. People didn’t just quote the ad — they used it as a greeting. It became less a slogan, more a ritual. Just a phrase, stretched into absurdity until it became impossible to forget. The beer was there in the background, but the ad gave people something more powerful: a sound they wanted to say with their mates.

“Whassup?!” changed everything because it proved that the right piece of culture doesn’t need spectacle. It doesn’t need a hard sell. It just needs to slip into your mouth and stay there. And for a few glorious years at the turn of the millennium, everyone was saying it.

Cadbury – “Milk Tray Man” (1968)

Advertising Agency: Leo Burnett London

“And all because the lady loves Milk Tray.”

The screen opens on a mountain at night. A man in black stands at the rockface. He dives into the sea, swims alongside sharks, sneaks onto a yacht — all with the stealth of a secret agent on a mission.

But he’s not here to kill, or to steal, or to save the world. He’s here to leave a box of chocolates for his woman.

This was the birth of the Milk Tray Man — Cadbury’s answer to James Bond. A lone figure risking life and limb, only to drop off a gift and vanish into the night. The tagline said it all: “And all because the lady loves Milk Tray.”

It’s absurd, really. Nobody needs a commando-trained stuntman to deliver confectionery. But the straight-faced seriousness was the gag. By treating chocolate as if it were worth espionage, sabotage, and cliff-diving heroics, the ad made Milk Tray feel like more than a box of sweets. It became a gesture. A symbol. A ritual of romance.

The campaign ran for three decades, spawning sequels, spoofs, and endless cultural references. But the original remains the purest: a daring man, a dangerous mission, and a reminder that sometimes the most surreal ideas are the ones played completely straight.

Levi’s – “Drugstore” (1995)

Advertising Agency: Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH London)

“Watch pocket created in 1873. Abused ever since.”

Michel Gondry shot it like a fever dream in first person. We’re the boy. Bells jangle as we shoulder open the pharmacy door. We drift to the counter, lean in, whisper our request. The pharmacist freezes, weighing us, then finally pulls a small metal tin from a locked cabinet. A mother nearby twists her child’s head away. We scoop it up, slip the tin into the tiny watch pocket of our 501s. Transaction complete.

The whole thing plays out inside our eyes — POV, tight, conspiratorial. The Biosphere soundtrack hums with secrecy. Until the final cut. For the first time, we see ourselves from the outside: arriving at a house, greeted by the pharmacist from earlier. Only now he isn’t just the man behind the counter. He’s also the father of the girl we’ve come to take out. And he knows exactly what’s hidden in that pocket.

The reveal snaps everything into place. It wasn’t jeans at all. The ad toys with perspective, the gag living in what we couldn’t see — until the twist delivers the punchline. The CTA lands like a smirk: “Watch pocket created in 1873. Abused ever since.”

That’s why Drugstore endures. It’s noir surrealism disguised as a Levi’s ad — selling rebellion by not selling jeans at all. A POV punchline that turned a tiny denim pocket into the most infamous hiding place in advertising history.

Directed by Michel Gondry. Music: “Novelty Waves” by Biosphere. Agency: BBH London (1995).

Guinness – “NoitulovE” (2005)

Advertising Agency: AMV BBDO

“Good things come to those who wait.”

Three mates stand at a pub bar, fresh pints of Guinness in hand. They raise their glasses, take a long pull… and the world jolts into reverse.

Clothes and city peel back through time — modern London to Edwardian streets, to an Anglo-Saxon settlement — before the landscape ices over. The men regress from Neanderthals to primitive hominids, then chimpanzees, and in a blink-fast montage become other creatures: flying squirrels, small mammals, aquatic shapes, fish, flightless birds, even little dinosaurs and burrowing lizards, until they’re mudskippers at a murky pool. One tastes the water and recoils.

It’s gloriously overblown — waiting not just for a pint to settle, but for all of evolution — and that swagger is what made it stick.

Director: Daniel Kleinman. Post: Framestore. Music: “Rhythm of Life” (Sammy Davis Jr.).

Old Spice – “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” (2010)

Advertising Agency: Wieden+Kennedy (Portland)

“Look at your man, now back to me.”

It opens with a dare: “Ladies.” A towel. A stare down the lens. Then the words start sprinting. Diamonds pour from a hand, a boat materialises, tickets become jewels, and reality keeps shifting without ever breaking eye contact. In half a minute we blow through three locations and six jokes, and land on the only line anyone remembers: “I’m on a horse.”

The charm isn’t just Isaiah Mustafa’s impossible calm — it’s the form. The spot is staged to feel like a single, continuous take: no hard cuts, just seamless transitions powered by meticulous practical effects (walls lifting, sets swapping, a hidden ride onto the horse) with a sprinkle of invisible VFX. It’s an escalation engine disguised as a body-wash ad.

And that was the sleight of hand. Old Spice didn’t explain benefits. It performed them. Confidence as theatre. Seduction as stand-up. The brand stopped trying to be cool and simply was — so shamelessly absurd it looped back to genius. Within weeks it was everywhere: parodies, late-night monologues, reply videos, a cultural chorus line quoting it back verbatim.

Ten out of ten for commitment, eleven for timing, and twelve for the exit. Because the only way to end a perfect ad — and this first volume — is on a horse.

Why the Weird Still Works

Across all of these, the trick wasn’t randomness — it was precision inside the madness. Tango’s replay. Gorilla’s drum fill. Mr Soft’s lamppost. Bravia’s physics. Frogs and Whassup’s repetition. Milk Tray’s straight-faced espionage. Levi’s POV reveal. Guinness rewinding all the way to mud. Old Spice’s impossible “one take.” Different flavors of surreal, same underlying discipline.

That’s the lesson: weird only lands when the craft is ruthless. Structure, timing, silence, music, camera — every choice tight enough to let the absurd feel inevitable. These ads didn’t explain themselves. They trusted us to keep up. We did.

If advertising is interruption, the greats interrupt your expectations first — then everything else. That’s why these thirty seconds still live rent-free. They bent reality just enough to become memory.

What Comes Next

This is only Volume One of Ads That Changed Everything. Next, we trade chaos for couture: Fashion as Fantasy — the spots that treated thirty seconds like cinema and fragrance like myth. Think Kenzo World, Cindy at the Pepsi machine, Chanel at its most operatic.

Same lens. New vibe. See you in Volume Two.