806 Hz & 1612 Hz: The Sonic Signature of the Spectrum 48K

I can still hear it—the first digital screech spilling out of the cassette deck, the Spectrum 48K in my bedroom on Chestnut Grove sparking to life. Jet Set Willy was the game, my initiation into a world that didn’t yet have the words “virtual” or “digital,” but felt like both. That room was massive—two beds, wardrobes, a desk with a couch that made it feel like a playground. My little brother was still too young to understand it, but I was lucky: I had space, time, and a machine that would shape who I became.

We weren’t startled by the sound. We’d already leaned over friends’ shoulders, their older brothers’ Ataris and Commodores teaching us that games came with a cost: patience. But when that high-pitched tone screamed in my own room, it wasn’t just noise. It was a portal. A doorway into new worlds we hadn’t seen before.

The waiting became part of the ritual. Halfway through, a loading screen appeared—pixelated art that felt like a promise. Dizzy’s adventures, Willy’s mansion; each game teased with a single image that sold a dream. We learned patience, and in that patience, anticipation. The beginning screech felt like ignition; the final tones, near the end, came with equal parts thrill and fear—would it finish, or crash and break our hearts?

Looking back, I wonder: were those tones doing more than we realized? Frequencies affect mood, healing, even body chemistry. Did the Spectrum’s binary shrieks teach us to focus, to wait, to dream in new shapes? Maybe those frequencies carried more medicine than we knew. What I do know is that the Spectrum 48K was my first teacher in tech. It taught me how to code, how computers worked, how machines could be bent toward art. That was the seed of my tech persona, planted in Wales by a screeching cassette player.

And maybe that’s why I wanted to write this—because what I chase at RIOT is the same thing those tones gave me: moments that cut so deep they become impossible to forget. We want our work to hit like that—to lodge in memory, to live forever in the psyche, to be legendary.

Back then, we laughed at the noise, danced to it even, while our parents rolled their eyes at sounds they couldn’t decode. Like the later dial-up tones, it was a secret signal of a generation—a screech that meant wonder is coming.

The Language of Machines

Before Wi-Fi, before SSDs, before progress bars, the Spectrum 48K spoke its data out loud. Every program was turned into a stream of tones, pressed onto cassette tape like a song. When you hit PLAY, you weren’t just feeding the computer numbers—you were letting it listen. Code became sound, and sound became code again.

The tones themselves were stark and mathematical, yet strangely alive:

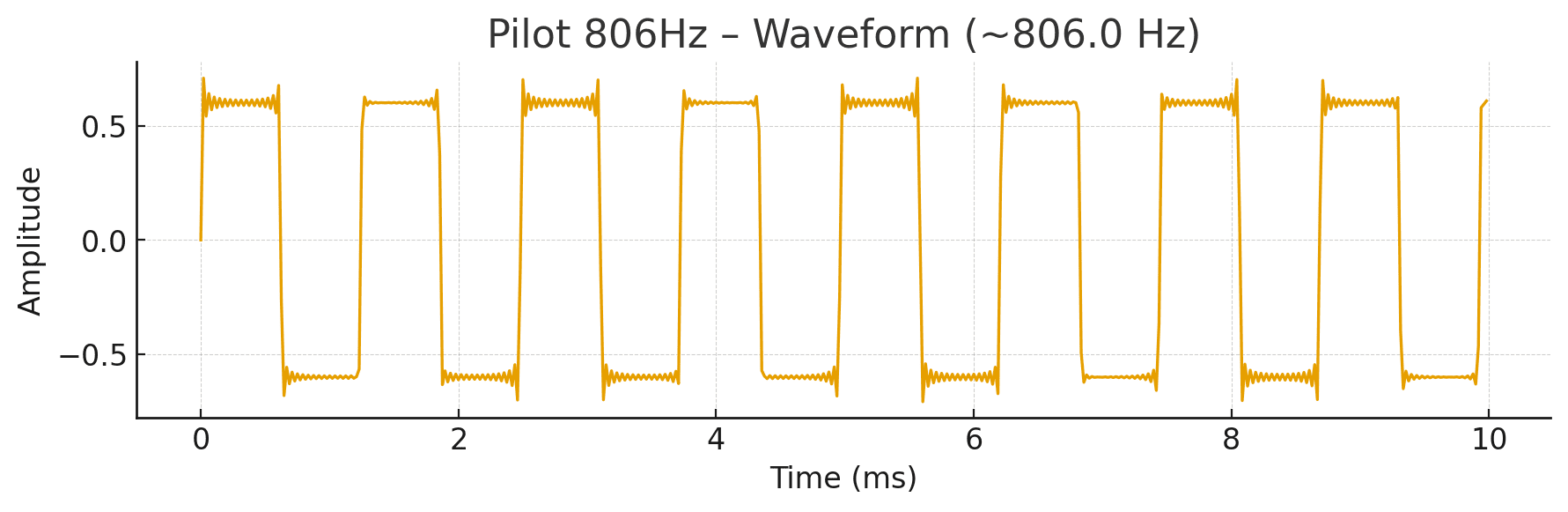

- The Pilot Tone: a steady whine around 806 Hz. This was the “are you there?” mantra, played long enough to sync the computer’s timing. To us it sounded like ignition—a piercing drone filling the room.

- The Sync Blips: two quick chirps, roughly 2.6 kHz and 2.3 kHz. They snapped the machine awake, like a conductor’s baton strike before the orchestra begins.

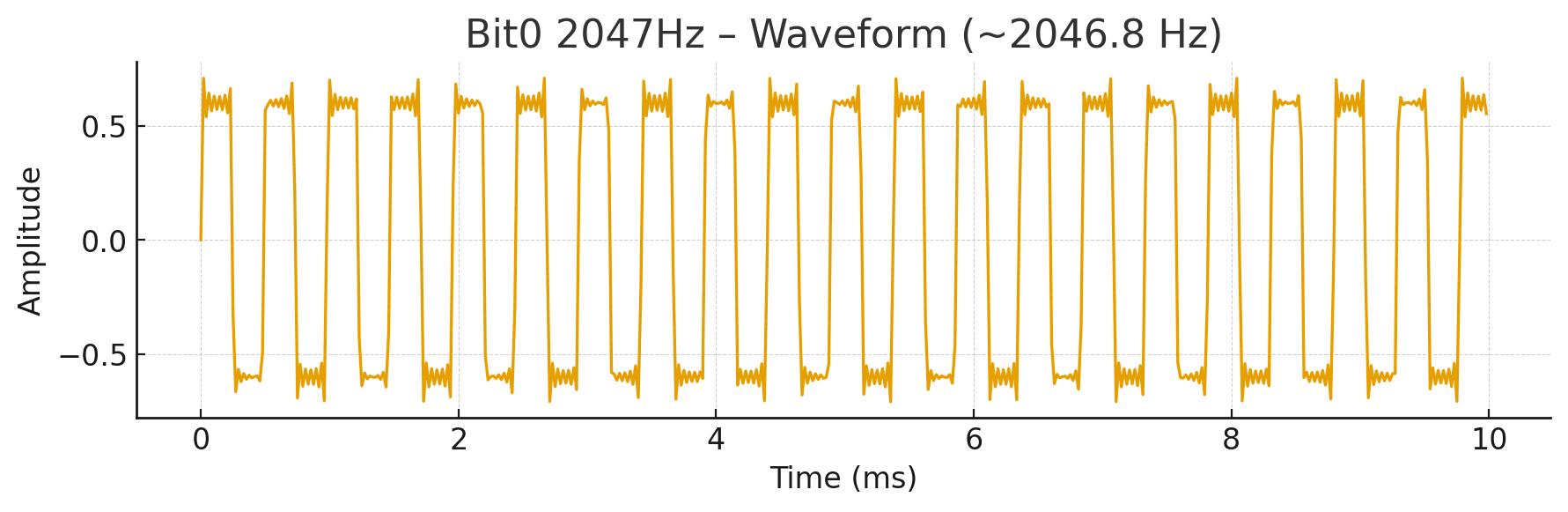

- Data Zero: pulses beating out around 2.05 kHz. Sharp, high, insistent—the sound of emptiness encoded as something jagged.

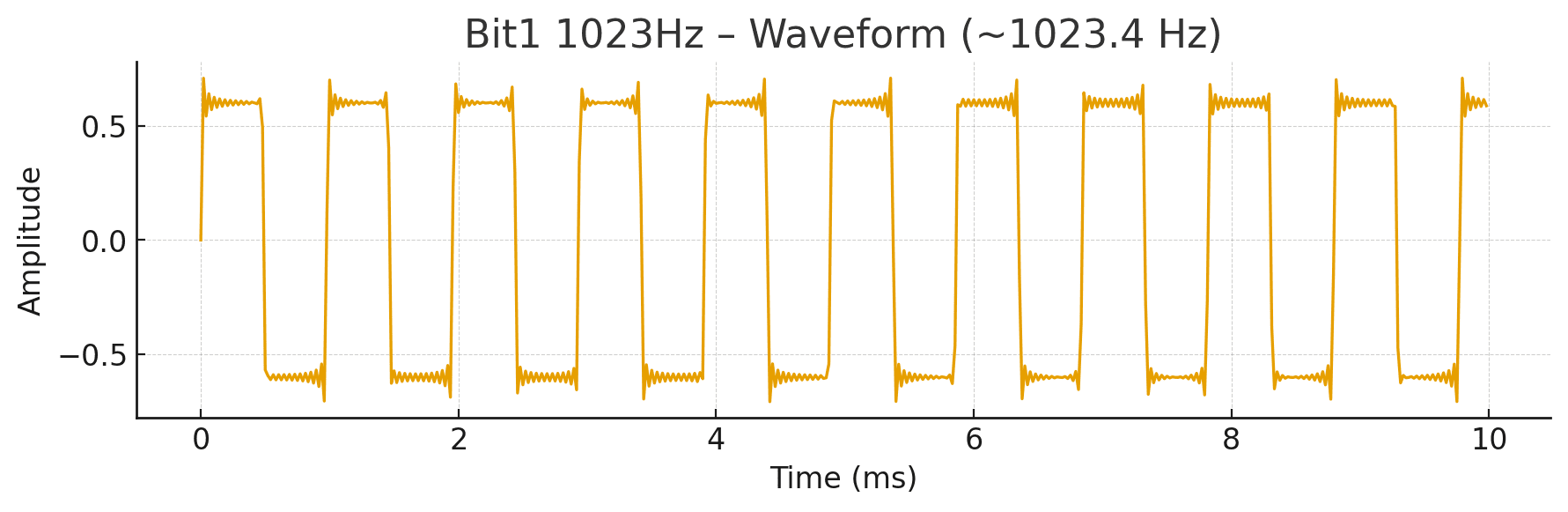

- Data One: pulses nearer 1.02 kHz. Lower, steadier, less shrill—the sound of fullness, slower cycles stretched into the tape’s hiss.

None of these were clean sine waves—they were square waves, full of rich harmonics. That’s why the loader felt like a swarm of angry bees instead of a polite beep. A 1.02 kHz “one” didn’t just sit at 1 kHz; it bled energy into 3 kHz, 5 kHz, 7 kHz, and beyond. That harmonic stack put power directly into the ear’s most sensitive band, the same region babies cry in and alarms are tuned for. No wonder it commanded our attention.

From a health and wellness perspective, the irony is beautiful: the engineers weren’t choosing frequencies to heal or alter mood, they were just trying to make decoding reliable on cheap cassette decks. Yet the result was unmistakably felt. Steady tones in the 800–2,000 Hz band keep the brain alert; their harmonics push into the “hot zone” of human hearing, increasing arousal and anticipation. Add the context—waiting for a reward, a new world to unfold—and the screech becomes charged with meaning, almost medicinal in its effect on focus and patience.

So the Spectrum wasn’t just crunching numbers; it was chanting in frequencies our bodies couldn’t ignore. A binary hymn in 806 Hz and 1,612 Hz, dressed in harmonics, whispering: hold on, wonder is coming.

Anatomy of a Load — When Noise Became Music

1. The Leader Tone (Ignition Drone ~806 Hz)

It begins with a piercing drone, a square wave locked around 806 Hz. To the Spectrum, this is just calibration — a metronome to sync its timing. To us, it felt like a ritual bell, filling the room with anticipation. The drone lasted long enough to make you restless, then just when you thought nothing would happen… it shifted.

2. The Sync Blips (The Wink ~2.6 kHz & ~2.3 kHz)

Two sudden chirps, around 2.6 kHz and 2.3 kHz, broke the monotony. These weren’t meant for us, but for the machine: a wink that said, get ready, the story is about to start. Our ears registered them as punctuation, like the conductor’s baton before the first note.

3. The Header Block (Identity Rhythm)

Next came a rhythm — metadata disguised as music. The Spectrum was loading the block’s name and length, but to our ears it was a stuttering beat, already closer to a melody than machine code had any right to be.

4. The Data Block (Glitch Symphony ~1.02 kHz & ~2.05 kHz)

Now the frenzy: a back-and-forth between two tones, one near 1.02 kHz, the other near 2.05 kHz. A “0” versus a “1.” Square waves buzzing with odd harmonics — energy at 3, 5, 7 times those base frequencies — making the sound harsher, sharper, alive. This was the heart of the screech, pure binary rendered as an alien chant.

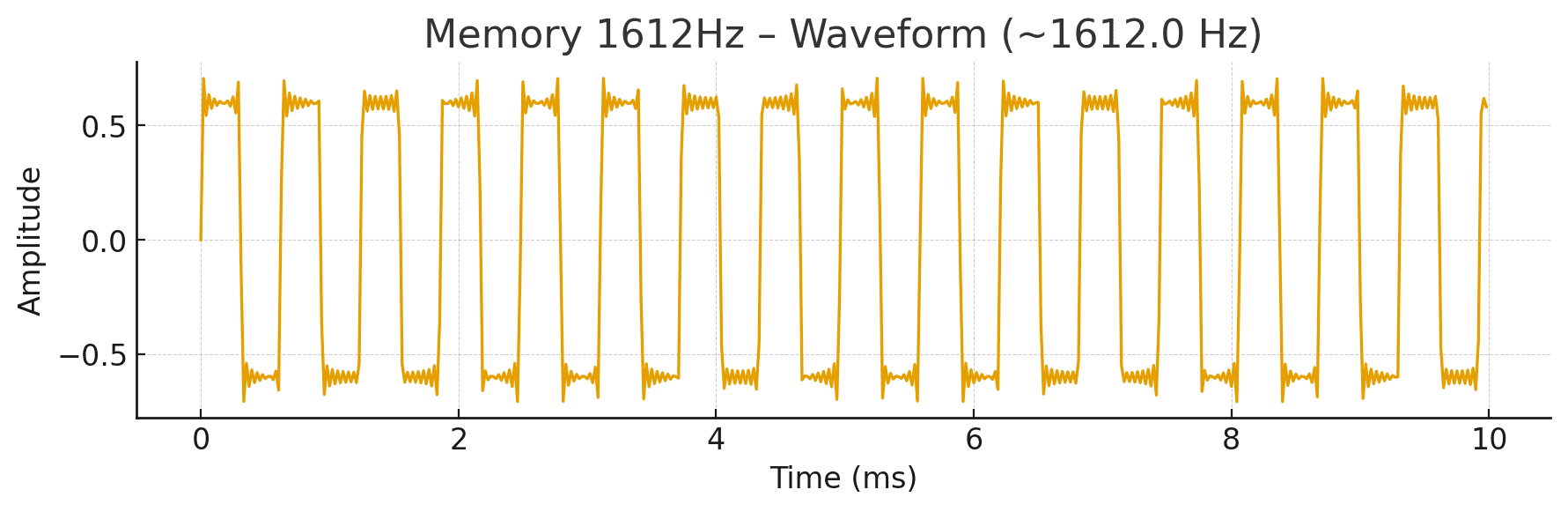

The Memory Tone (~1.612 kHz): While the official loader lived at ~1.02 kHz and ~2.05 kHz, many of us remember hearing something closer to 1.6 kHz. That phantom pitch came from a mix of tape drift, turbo loaders with custom timings, and the harmonics of square waves stacking energy in that band. It’s the “memory tone” that still rings in our heads today — the pitch of anticipation, etched into nostalgia.

5. The Pause (The Drop)

Then silence. Just tape hiss and whirring reels. After the chaos, the absence of tone hit harder than any note. Every kid leaned in. Would it continue? Or had it failed? The silence was its own instrument — suspense made audible.

6. The Next Movements

More blocks followed, each with slight shifts in rhythm or pitch drift. Our ears didn’t know the technical cause, but our hearts recognized them as verses, variations in the song. Even glitches in tape speed felt like improvisation.

7. The Final Chirp (Resolution)

When the last block finished, the screech cut and the screen shifted. Relief. Triumph. Sometimes heartbreak — because the cruelest failure was one that collapsed right at the end. That moment was burned into us: the final tone as catharsis or as tragedy.

Failure, Corruption & Chaos

Loading wasn’t guaranteed. Every kid knew the gut punch: you’d sit through five, ten minutes of screech and static, only for the Spectrum to cough out an error. The screen froze, the tones collapsed, and hope died in silence. Sometimes it failed instantly, sometimes it betrayed you at the very end — the cruelest fate of all.

Those failures had their own sound. The clean alternation of ~1.02 kHz and ~2.05 kHz would stumble, distort, and smear as the tape head slipped or alignment drifted. The square waves broke apart into unpredictable bursts — part tone, part noise. It was accidental noise music, proto-industrial sound art before we even knew such words existed. What we called frustration, someone else might have called a performance.

Corrupted loads felt alive in their own way: strange harmonics clawing at the air, fragments of binary half-decoded. These glitches were chaotic, yes, but also strangely beautiful. They taught us early that failure has a sound — a raw, jagged reminder that technology is never perfect, and that imperfection itself can carry feeling.

Maybe that’s why so many of us grew to love distortion, glitch, and noise in later music and art. We had already heard it in our bedrooms as children, pouring out of cassette decks that were trying, and failing, to make magic.

We swore it had a beat. The Spectrum’s loader wasn’t written as a song, yet our ears kept finding rhythm inside the chaos — a kind of proto-techno born from square waves and waiting. The loader spoke in loops. A long pilot drone around ~806 Hz, then patterned bursts (header), then torrents of alternating bits at ~1.02 kHz and ~2.05 kHz. Even though those frequencies are far above “tempo,” their patterns repeat at human timescales — blocks starting and stopping, clusters of similar bits arriving in runs — which our brains happily round down into pulse and groove.

Real cassette decks wander. Tiny speed variations (wow/flutter) bend the pitch a hair, turning steady tones into a gentle vibrato. The pilot can feel like it’s “sailing,” and the data duet (~1.02/~2.05 kHz) can smear into the remembered ~1.6 kHz memory tone. That breath of motion reads as musicality — like a synth held just off center so it shimmers. Square waves are rich in odd harmonics (3×, 5×, 7×…). Stack those overtones into the ear’s hot zone (2–5 kHz) and you get a bright, buzzy timbre. Slight tape drift shifts those partials against each other, creating slow beat patterns — a natural chorus that feels like a rhythm section hiding inside the screech.

Many games ditched the stock ROM timings for custom or “turbo” loaders — faster pulse widths, different ratios, sometimes higher fundamentals. To us, that meant snappier, tighter, more percussive sequences. Same binary alphabet, new phrasing. It’s why some loads felt punchy while others felt droney. The structure itself plays like a track: drone (intro), sync blips (count-in), header rhythm (overture), data frenzy (chorus), sudden silence (the drop), then the next movement. That choreography of tone → pause → tone is classic tension-and-release — musical by design of the process, not intention of the composers.

Halfway screens, border flicker, tape-reel whirr — the audiovisual stack locks your brain into a loop. The sight of pixels forming while the ~806 Hz drone or the ~1–2 kHz duet grinds on becomes entrainment. You’re nodding before you notice. So no, it wasn’t written as music. But repetition, drift, harmonics, structure, and context conspired to make it feel like music. The Spectrum didn’t just load; it performed.

From Spectrum to Dial-Up — The Sonic Lineage

The Spectrum 48K wasn’t the last time machines sang their work out loud. The same children who grew up with cassette screech would later meet the shriek of the 56k modem — a handshake chorus of shifting tones and bursts of white noise that meant you were online. Different pitch, same ritual: an alien language of machine-to-machine communication that doubled as the soundtrack of anticipation.

That lineage is clear: the ~806 Hz pilot drone became the steady warble of carrier signals; the binary duet of ~1.02 kHz and ~2.05 kHz echoed in modem bursts; the sudden silences mirrored in the moments between handshake phases. We learned to trust noise as a promise. The wilder the sound, the closer we were to connection.

And then… silence. Broadband, fiber, Wi-Fi: faster, seamless, frictionless. Downloads became invisible, progress was measured in percentages instead of screeches. We lost the ritual of listening, the physical patience of hearing a world load itself into existence. Machines grew quieter, but in that quiet, they also became less felt.

Maybe that’s what made those earlier sounds unforgettable. They weren’t background—they were front and center, unavoidable, woven into the ritual of discovery. Today, technology is instant and invisible. Back then, technology sang to us.