Dylan Thomas’ Rebellion: A Journey Through Welsh Poetry, Life, and Death

There are poets who speak to your soul, and then there are poets who give your soul a voice. Dylan Thomas was the latter, a flame that never stopped burning, igniting creativity across generations and continents. For me, Thomas isn’t just a poet from the past; he’s a constant companion, whispering words of rebellion, life, and death, shaping the very language I use to create.

As a fellow Welshman, I’ve always felt an unspoken connection to his world. The rugged, windswept landscapes of Wales have a rhythm of their own, and it was in those landscapes that I first found my creative spirit. Summers spent in a caravan on the Gower Peninsula, with the sea roaring like Thomas’ verses—it was impossible not to feel the pull of something deeper. That rhythm stayed with me, followed me across the Atlantic to New York City, where, like Dylan before me, I found my voice in the vibrant chaos of the city’s streets.

Thomas’ work was never about taming the wild—it was about embracing it. In every line, there’s a sense of urgency, of life being lived in its most raw and unfiltered form. His poems rage against complacency, against surrender. They speak of love and death, yes, but also of defiance, of the refusal to let life slip quietly into the night. In many ways, that’s the same energy we channel at RIOT—creative rebellion, daring to push boundaries, refusing to conform.

This is not just an exploration of a poet; this is a personal journey into the soul of a man who, to me, is as relevant now as he was when he first put pen to paper. His words have shaped my world, and through this, I hope they might shape yours too.

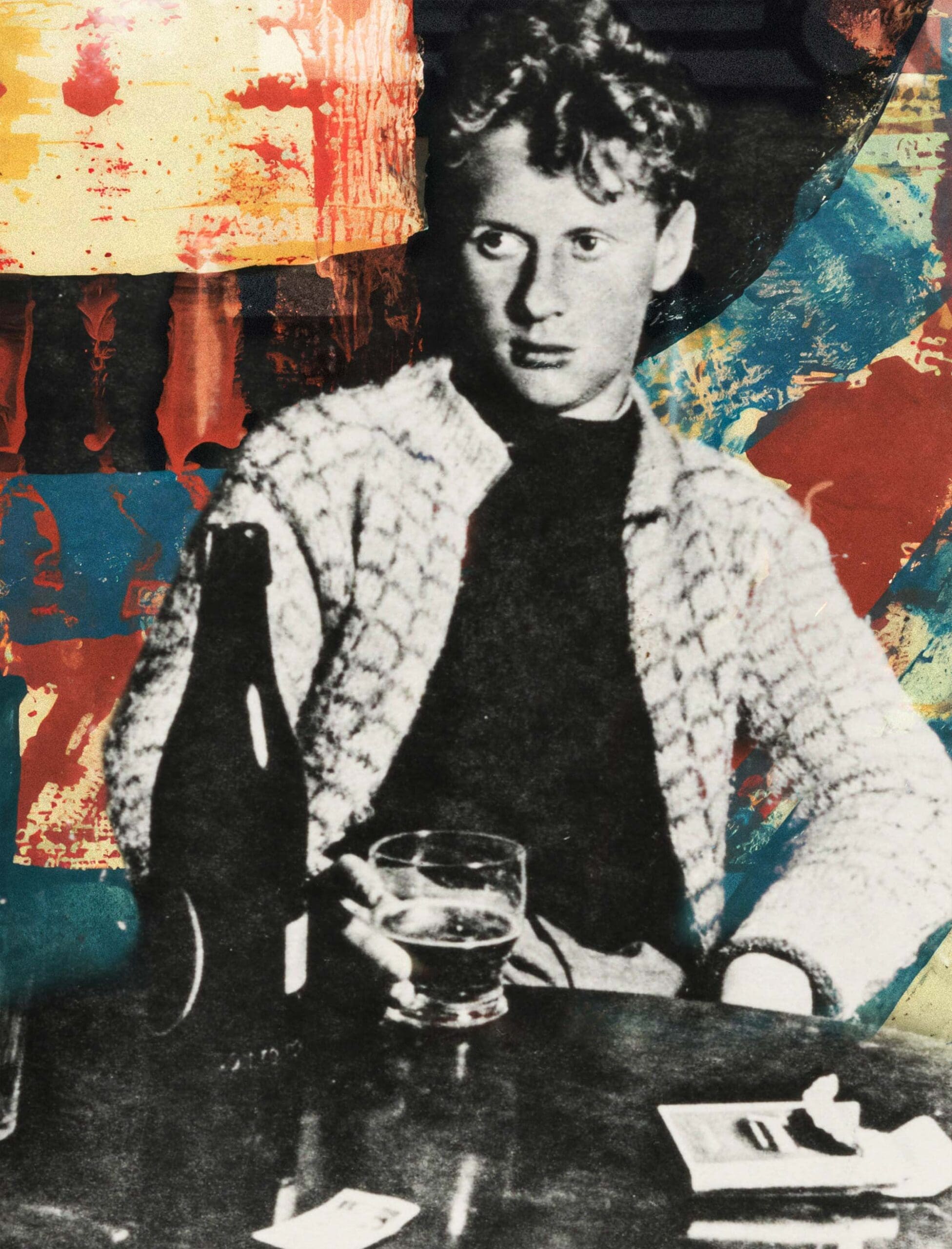

Artwork based on a vintage photograph of Dylan Thomas drinking a pint in a Welsh pub. Original photo by Rosalie Thorne McKenna, adapted and remixed under the terms of the CC BY-SA 4.0 license. Artwork by MUG5.

“Somebody’s boring me. I think it’s me.” — Dylan Thomas

All photos of Wales shown throughout this article are pieces of work that I created or captured myself. Each image is a visual ode to Wales, a tribute to the landscapes that shaped both my creativity and Dylan Thomas’ timeless poetry.

Foreword by RIOT Executive Creative Director and Founder Chris “MUG5” Maguire

A Child of the Wild West: Dylan Thomas and the Call of Wales

Dylan Thomas was born in Swansea, Wales, in 1914, and from his earliest days, the rugged beauty of the Welsh countryside played a key role in shaping his imagination. Much like the unpredictable Welsh weather, his childhood was filled with a combination of joy, isolation, and wild freedom. It was this landscape that would echo throughout his work, a constant reminder of the untamed nature of both the land and the soul.

A misty morning on a Welsh country road, photographed by MUG5 for this article. All photos throughout are a visual ode to Wales, paying homage to the landscapes that inspired Dylan Thomas.

For Thomas, the wilds of Wales weren’t just a backdrop—they were his muse, his rhythm, and his rebellion. The lyrical quality of the Welsh language, even though he famously did not speak Welsh fluently, was present in every line he wrote. The cadence of the land, its winds, and its storms infused his poetry with a musicality that is unmistakable. His early years spent roaming the Gower Peninsula, the same rugged coast where I spent my summers, became the foundation for the emotional landscapes he would later explore in his work.

Thomas’ family home in Cwmdonkin Drive was a place of books, language, and creativity. His father, a schoolteacher, introduced him to the works of Shakespeare, sparking his lifelong obsession with the sound of words. Thomas’ early poems were an exploration of both life and death, love and loss—central themes that would define his work and align with the inherent duality of the Welsh spirit. The duality of the Welsh landscape, from the raw cliffs of the Gower to the tranquil hills of the countryside, is reflected in his writing, full of both tenderness and violence.

It was in these early days that Dylan Thomas began to define his poetic voice—a voice that was deeply Welsh, yet universally human. His work was never just about Wales, but about the raw, unfiltered experience of life itself. This is where Thomas’ connection to both the land and the language becomes more than just background—it becomes the heartbeat of his poetry.

“I hold a beast, an angel, and a madman in me, and my enquiry is as to their working, and my problem is their subjugation and victory, downthrow and upheaval, and my effort is their self-expression.” — Dylan Thomas

It’s in these words we find his personal rebellion—against tradition, against expectation, and against a world that sought to contain his creative fire. Wales was his fuel, and his poetry, his rebellion.

Echoes of Chaos: Thomas’ Literary Influences and Inspirations

From the very beginning, Thomas was drawn to writers and thinkers who challenged the status quo. His father’s love for Shakespeare and the rhythmic language of the Bard left a lasting imprint on Thomas, shaping his early fascination with sound over sense. This obsession with the musicality of words became one of the defining characteristics of his work.

1623 engraving of William Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Yet, Thomas was more than just a product of his early environment. He voraciously consumed the works of the great modernists—writers like James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and W.B. Yeats, whose mastery of language and form helped shape his own poetic sensibilities. From Joyce, Thomas learned the power of stream of consciousness, the ability to craft fluid narratives that mirrored the human mind. From Lawrence, he embraced the wild, untamable nature of desire and rebellion. Yeats’ use of symbolism and myth wove itself into Thomas’ own work, particularly in the ways he approached themes of mortality and transcendence.

It wasn’t just established figures that fed Thomas’ fire. He was just as influenced by contemporary peers, particularly other poets who were pushing the boundaries of what poetry could be. T.S. Eliot, whose dense, allusive style captivated readers of the time, represented another modernist force that Thomas respected. But while Eliot’s work could feel cerebral and detached, Thomas’ poetry was visceral—born from the gut, not the mind.

Thomas’ influences weren’t confined to literature. His time in Swansea exposed him to a rich tradition of oral storytelling, a practice that has deep roots in Welsh culture. The cadence and flow of these oral traditions, much like the Welsh language itself, found their way into Thomas’ work. His poetry, with its internal rhymes, alliterations, and repetitions, mimics the oral storytelling practices of Wales. Even as Thomas rebelled against tradition, he was still carrying fragments of tradition with him in every line.

“I’ve always had a fascination with Dylan Thomas. He was an angry man, and a great writer who wrestled with life and death. His poetry stirs the soul.” — Anthony Hopkins

As we explore Thomas’ influences, we’re reminded that creativity is never created in a vacuum. Every artist is a composite of the voices they’ve absorbed, the landscapes they’ve wandered, and the stories they’ve heard. And through understanding those influences, we open ourselves up to discovering new ones, creating our own echoes of chaos. Like Thomas, we at RIOT are always searching for those threads of rebellion, rhythm, and raw humanity in the creative process—constantly learning from those who came before while forging our own path forward.

A beautiful Welsh mountain landscape captured by MUG5 for this article. All photos throughout are part of a visual ode to Wales, highlighting the natural beauty that influenced Dylan Thomas’ poetry.

Poetry of the Street: Dylan Thomas in New York City

For Dylan Thomas, New York City was more than a destination—it was a catalyst. After years of living in the Welsh countryside, the streets of Manhattan injected a new kind of energy into his work, pushing him to new creative heights. Much like the sea that roared through his Welsh childhood, New York was a force of nature. It was chaotic, vibrant, and unapologetic—qualities that resonated with Thomas’ own rebellious spirit.

When Thomas arrived in New York in 1950, he found himself in a city that was alive with culture, ideas, and creativity. It was a far cry from the misty hills of Wales, but in the noise and rush of the city, Thomas found a new voice. His performances at venues like the 92nd Street Y became legendary, where his readings captivated audiences with the musicality of his words. His time in New York marked a high point in his career, but it also introduced him to the darker sides of fame and excess.

Much like Thomas, I found my own creative spirit in New York. The city has a way of forcing you to define yourself amidst the chaos, to find your own voice in the whirlwind. In many ways, Thomas’ journey mirrors my own experiences with RIOT. His poetic explorations in New York were charged with the same defiance and raw energy that I strive to bring to everything I create. It’s about taking that sense of rebellion, of fighting against the noise, and turning it into something meaningful.

A glimpse of the New York City skyline, captured by MUG5. Just as Dylan Thomas found creative energy in these streets, this city continues to fuel our rebellion at RIOT.

New York wasn’t just a backdrop for Thomas—it became part of his creative DNA. The city’s influence can be felt in his later works, where the intensity of urban life collided with the natural rhythms he had always known. Whether in a bar in Greenwich Village or walking along the East River, Thomas absorbed the city’s pulse. His poetry, much like the city itself, became louder, more urgent, and unapologetically alive.

But with that energy came a heavy cost. The city that fueled Thomas’ creativity also contributed to his downfall. His time in New York was marked by nights of heavy drinking, and it was here that his health began to rapidly decline. By the time of his death in 1953, the city had left its indelible mark on him—both as an artist and as a man. Despite the chaos, or perhaps because of it, Thomas’ work remains a testament to the creative power of New York, a place that, like the Welsh sea, shaped and scarred him in equal measure.

A Raging Fire: The Wild Spirit Behind Dylan Thomas’ Greatest Works

If the streets of New York were the stage, then Dylan Thomas’ poetry was the performance. At the height of his career, Thomas gave the world some of his most unforgettable works—pieces that not only cemented his place as one of the 20th century’s greatest poets but also showcased the wild, untamed spirit that burned within him.

Perhaps his most famous poem, “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night”, stands as a defiant anthem against the inevitability of death. Written during one of the most turbulent periods of his life, this poem is not merely a reflection on the passing of his father—it’s a call to arms, a raging against the dying of the light. Its structure, a villanelle, with its relentless repetition and strict rhyme scheme, mirrors the struggle Thomas faced—both creatively and personally. The poem is raw, urgent, and fierce—a perfect embodiment of Thomas himself.

“Dylan Thomas’ work doesn’t let us forget the untidiness and pain of human life. His poetry is a wild dance with death, full of anger and wonder.” — Rowan Williams

Another masterpiece, “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”, takes a different approach. Rather than fighting against death, this poem offers a sense of peace and acceptance, a reminder that even in death, there is a kind of immortality. Its biblical allusions and lyrical repetitions reflect Thomas’ deep connection to both the natural and spiritual worlds. It’s a poem of defiance, but of a quieter kind—one that acknowledges the cycle of life and death as something more than just an ending.

Dylan Thomas’ Writing Shed in Laugharne. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

What’s fascinating about these works is the duality they represent. On one hand, Thomas was a man who raged against everything—society, expectation, mortality—but on the other, he was deeply introspective, embracing the beauty in life’s fleeting moments. His ability to capture this tension between rebellion and acceptance is what makes his poetry so resonant, even today.

Thomas’ poetry wasn’t about neatly packaged meanings. It was about sound, rhythm, and emotion. His lines were meant to be spoken aloud, shouted into the wind, or whispered under your breath. In that way, his poetry continues to rebel against traditional structures. Thomas’ greatest works live on, not just in the pages of anthologies, but in the hearts of creatives everywhere who dare to defy the expected, who push against the dying of their own light. Like Thomas, we too can burn fiercely, refusing to go gentle into any good night.

The Graveyard: Death and Mortality

Death was never far from Dylan Thomas’ mind. It’s a recurring theme in his work, and rather than being something to fear, Thomas approached death as a part of life’s ongoing cycle—a force to be reckoned with, yet accepted. From his earliest poems to his most famous works, death looms large as both a foe to be fought and an inevitability to be embraced. This constant push and pull between life and death, between creation and destruction, was something that shaped his worldview, as seen in his poetry.

Welsh Graveyard – an atmospheric photograph by MUG5, capturing the eerie beauty of an ancient Welsh graveyard. The image evokes the themes of life, death, and legacy found in Dylan Thomas’ poetry.

In his renowned poem “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”, Thomas confronts death head-on, using biblical allusions to challenge the finality of mortality. The poem’s repetition and lyrical rhythm create a feeling of defiance, almost as if the words themselves are pushing back against the concept of death. Rather than resigning himself to the idea of oblivion, Thomas presents death as a passage rather than an end—a moment where the human spirit is freed from its earthly constraints. Thomas often discussed his poetic philosophy around life, death, and immortality. He viewed death as a transformation rather than a final end, reflected in the cosmic and biblical imagery in this poem. For example, Thomas believed that the dead were not gone but rather became part of the universe—an idea he vividly conveys.

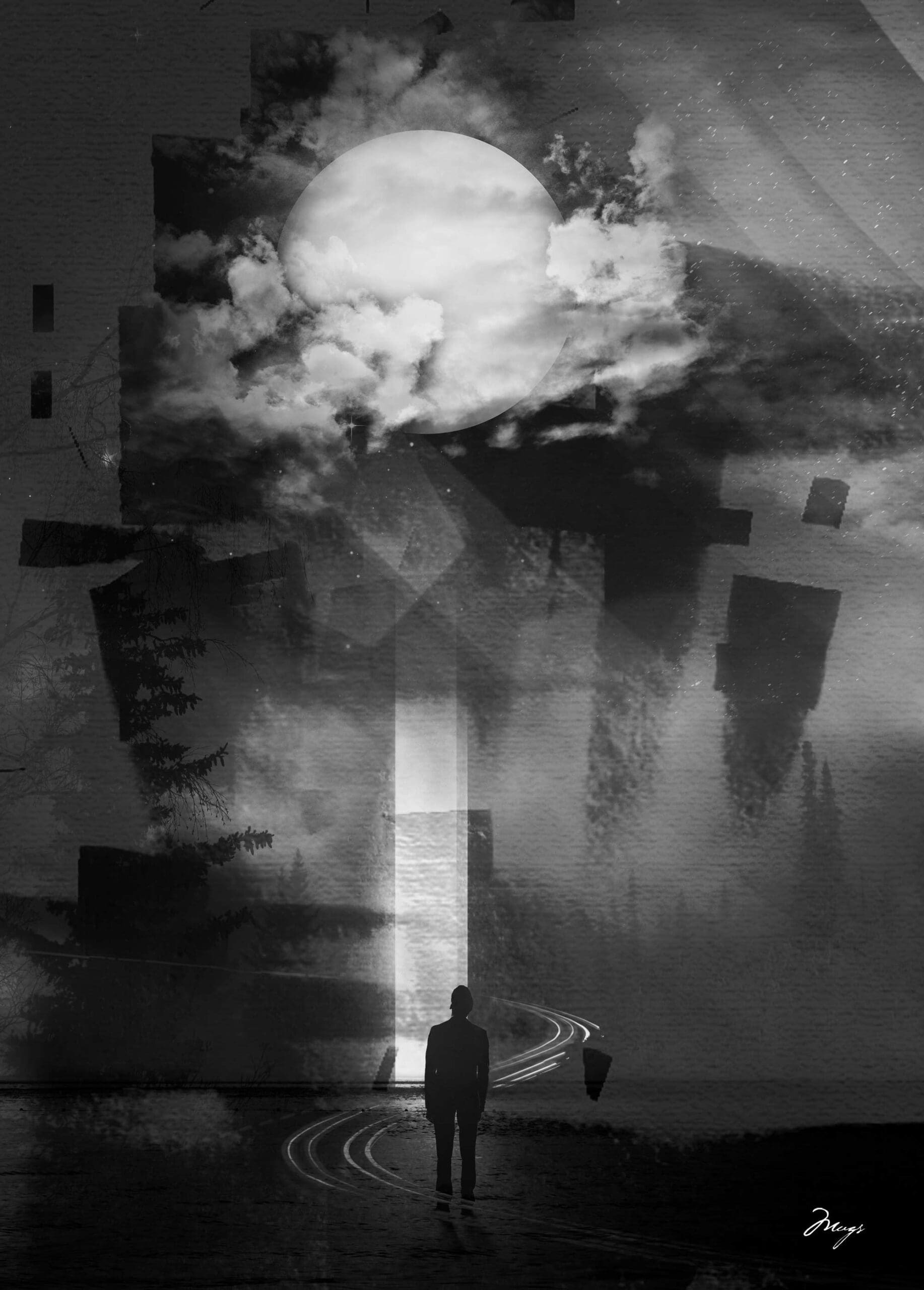

In the Cold I’m Standing – an original digital art piece by MUG5. This piece explores themes of isolation and introspection, aligning with Dylan Thomas’ poetic themes of life, death, and existential reflection.

“They shall have stars at elbow and foot; though lovers be lost, love shall not.” — Dylan Thomas

Similarly, “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” is perhaps the ultimate declaration of resistance. Written during his father’s illness, the poem rages against the quiet acceptance of death, urging the reader to fight until the very last breath. It’s a poem filled with urgency and emotion, one that reflects Thomas’ own internal battles. The villanelle’s repetitive form mirrors the cyclical nature of life and death, as if each stanza is a new wave crashing against the shore of inevitability. In an interview, Thomas spoke of his father’s influence: “He was the one who first made me aware of words and language, the rhythms of poetry, and how language can live and die in a moment.” That understanding of life’s brevity is echoed in both his work and his philosophy. For Thomas, death wasn’t just the end, but a transformation, a shift in the narrative.

But for all his defiance, Thomas also understood that death was an integral part of life. In many of his poems, death is a quiet presence, something that lurks in the background even in moments of joy. In “Fern Hill,” for example, Thomas reflects on his own childhood, filled with images of light and innocence, yet haunted by the knowledge that youth is fleeting. In that way, his work grapples with the tension between life and death, constantly shifting between rebellion and acceptance.

Destroy – an original digital artwork by MUG5, reflecting themes of decay, destruction, and rebirth. A visual dialogue with Dylan Thomas’ poetry, which often wrestles with the cycle of life and death.

“The function of poetry is to strip away the veils of illusion and show life as it truly is: raw, beautiful, and filled with an endless yearning to survive.” — Dylan Thomas

His exploration of mortality wasn’t just about death—it was about life. In embracing the fragility of existence, he found a deeper appreciation for the beauty in each moment. His work, much like life itself, is a balancing act between despair and joy, between fighting and surrendering. It’s that duality that makes his poetry so enduring, and it’s why his legacy will never fade.

A Song of the Land: Welsh Culture and Language in Dylan Thomas’ Poetry

Much like the hills and cliffs of his homeland, the Welsh language created a foundation that Dylan Thomas would build upon, layer after layer, to create his unique poetic voice. In Welsh culture, storytelling has always been more than just a pastime—it’s a way of life. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, shaped the way stories were told, with each teller adding their own rhythm, pace, and emphasis. This practice is reflected in Thomas’ poetry, where internal rhyme, alliteration, and repetition mimic the flow of a storyteller’s voice. His poems feel alive, as though they are meant to be spoken aloud, reverberating off the hills and valleys of Wales.

Welsh Valley – an original landscape photograph by MUG5, capturing the beauty of the Welsh countryside that influenced both my creativity and Dylan Thomas’ timeless poetry.

“He was a force of nature, a genius who spoke in the tongues of fire. In his words, we find the echoes of Wales, but his voice reaches far beyond.” — R.S. Thomas

Even though Thomas did not write in Welsh, the language’s influence on his poetry is undeniable. The Welsh word ‘hiraeth’—a sense of deep longing for home or a place that no longer exists—can be felt in many of Thomas’ works. This connection to the land and its people was at the heart of his writing. In “Fern Hill,” for example, Thomas’ nostalgic reflections on childhood are imbued with this very sense of hiraeth, a longing for the innocent days spent in the Welsh countryside.

Fairytale-like Forest – an ethereal photograph by MUG5, capturing the mystical beauty of a lush Welsh forest. The image conjures up the magical landscapes that inspired Dylan Thomas’ connection to nature and storytelling.

“Dylan Thomas is not only one of Wales’ greatest poets but a poet of the world. His words still resonate because they explore the rawness of life—beauty, pain, love, and loss.” — Ifor ap Glyn

For me, this connection runs deep. The rhythmic pull of the Welsh language, even without speaking it fluently, still influences the way I create. It’s in the landscapes of Wales, in the stories of the land, and in the lyrical echoes of the language itself.

A Rebel’s Legacy: Dylan Thomas’ Influence on Modern Creatives

Though Dylan Thomas passed away over seventy years ago, his legacy burns brighter than ever. From poets and musicians to filmmakers and visual artists, Thomas’ influence can be felt across generations. His refusal to conform to traditional poetic forms and his obsession with sound and rhythm laid the groundwork for many modern artists who also seek to break boundaries in their own work.

One of the most notable figures to draw inspiration from Thomas is Patti Smith, the godmother of punk rock. Smith has frequently cited Thomas as a major influence, not only in her writing but also in the defiant energy she brings to her music. His emotional depth and use of language to express human vulnerability are traits that resonate in Smith’s lyrics and performances. Similarly, Bob Dylan—born Robert Zimmerman—famously took his stage name as a tribute to Dylan Thomas, acknowledging the poet’s revolutionary approach to words.

Thomas’ impact extends beyond music into the visual arts as well. His defiance against the constraints of form can be seen in the works of modern visual artists, who use surrealism and abstraction to echo the way Thomas used words to evoke feelings rather than clear meanings. Much like Thomas’ poetry, their work often seeks to evoke an emotional response rather than offer a straightforward narrative. Thomas didn’t just influence artists and creatives; he also left a mark on the way people think about art and poetry itself. By rejecting the constraints of meaning, he opened up a new way of understanding art as something to be felt rather than dissected. His legacy lives on in every artist, musician, or poet who refuses to be boxed in, who lets their work speak with a voice that is raw, unfiltered, and defiant.

A Final Flame: A Tribute to Dylan Thomas

Dylan Thomas lived and died with fire in his veins. His life may have been marked by turbulence, but his words burn on—an eternal flame that continues to inspire rebellion, beauty, and defiance. His poetry isn’t something that lives in dusty anthologies; it’s alive in the streets of New York, in the wilds of Wales, and in every artist who dares to break the mold.

For me, Thomas’ work is more than an influence—it’s a call to arms. His defiance of tradition, his relentless exploration of life’s fleeting beauty, and his refusal to go gentle into any good night are reminders of what it means to live and create authentically. At RIOT creative agency, we carry that torch. Like Thomas, we aim to live fiercely, create fearlessly, and leave a lasting legacy that refuses to fade.

As Thomas once wrote, “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower / Drives my green age.” That force—the drive to create, to rebel, to live with intensity—is the pulse of everything we do. And like him, we too refuse to go gently.